By Alessandra Diaz

During the summer of 2023 CWRGM co-director Dr. Lindsey R. Peterson delivered a talk on digital scholarly editions to the New-York Historical Society’s Student Historian Internship Program. After attending the talk, Alessandra Diaz, a high school student from Queens, New York, joined the Civil War & Reconstruction Governor of Mississippi project’s transcription and subject tagging team, where she performs quality review of the collection’s transcriptions and adds enhanced discoverability features to improve users’ ability to access the site’s diverse collection of documents. As part of her internship, Diaz authored the following blog post on early debates over African American collegiate education at Alcorn University in Mississippi. A thought-provoking examination of the connections between education and racial uplift, Diaz explores applying the contemporary concept of equity to reframe how we conceptualize early HBCUs and offers a thoughtful personal assessment of historic approaches to African American educational civil rights during Reconstruction.

Many supporters of historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) typically believed they played a vital role in the advancement of African American civil rights. The institutional end goal was achieving equity—in this case providing freed people with support tailored to their unique needs rather than providing Black Americans the same kind of support white students received. Equality, on the other hand, proposed the same treatment for all groups regardless of their histories or current struggles. In the late-nineteenth century, HBCUs created spaces tailored to free African Americans’ experiences and identities at a time when they had limited access to educational spaces and the archetypal predominantly white institution did not serve African American interests.[1] The Civil War and Reconstruction Governors of Mississippi Project (CWRGM) collection reveals tensions between white lawmakers and African Americans about Black strategies for advancement, especially those employing racial uplift and respectability politics. These tensions surrounding HBCU Alcorn University demonstrate long standing debates over Black calls for more equitable treatment during Reconstruction. Both the reactions and their contexts highlight how white legislators used their lawmaking influence and how African Americans took charge of their agency to affect greater change in education.

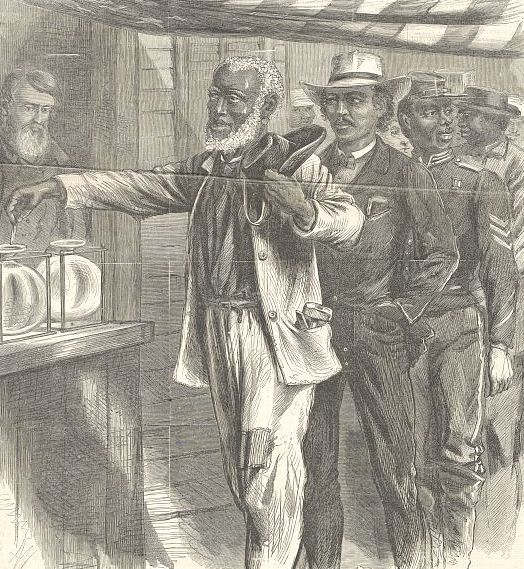

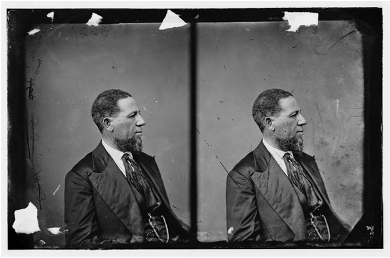

According to author and former Mississippi HBCU Alcorn University President (2011–213) M. Christopher Brown II, HBCUs create space for students to “develop a unique competency” in addressing minority-majority issues.[2] This concept, which he wrote about a decade before his tenure at Alcorn, embodies the equity that HBCUs championed: providing a curriculum specific to African American needs. During Reconstruction, African Americans were driven by these “unique competencies” to vote African Americans into office and argue for equity at the state and national level. Such was the case with the 1870 election of Mississippi politician Hiram H. Revels, the first African American United States senator. Using their voting power and education, they affected change on a local, state, and national level. Senator Revels, for instance, publicly opposed an amendment that would keep Washington, D.C. schools segregated. He contributed extensively to Reconstruction efforts in Mississippi, especially African American advancement through education. Following his term in the U.S. Senate, he even became the first president of Alcorn University (now Alcorn State University), an HBCU founded in Alcorn County, Mississippi in 1871 by white Mississippi Governor James L. Alcorn.[3]

Throughout the 1870s, African American voices from men like Senator Revels were present both in Congress and out of it. Organizations such as the American Missionary Association (AMA) funded primary and secondary-level schools beginning in the 1860s for the formerly enslaved to provide them with housing, a Christian education, and opportunities to assimilate into white society. While conforming to white society’s expectations of “civil” Blackness was at the root of respectability politics, many African Americans turned their newfound education and skills into new levels of autonomy, be it through opening their own businesses or entering activism, among other approaches.[4] The politics of respectability reflected in the AMA’s mission to integrate African Americans into white society, is a complex yet important legacy of organization-based emancipation efforts.

It is important to note that opportunities were not equal for all. Lawmakers established schools for African American women, but respectability politics impacted African American women in even more complex ways.[1] In her analysis of Southern Baptist African American women’s activism, historian Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham find Black club women’s activism was grounded in respectability politics. “From the perspective of the Baptist women and others who espoused the importance of ‘manners and morals,’ the concept of respectability signified self-esteem, racial pride, and something more,” she writes. “It also signified the search for common ground on which to live as Americans with Americans of other racial and ethnic backgrounds.” Consequently, women debated at conventions how best to implement moral standards in their communities.[5] Founded in the 1830s, Oberlin College in Ohio, was one of the first colleges to award diplomas to Black women at the undergraduate level following the Civil War. Most were primarily educated in the North as few coeducational, racially integrated schools existed in the South.

African Americans who identified as representations of the race identified themselves as “race” men and women, and there were further tensions within the African American community regarding the best approaches to advancement and education as well. When Revels left the university in 1874, Alcorn went through a period of transition, and Mississippi Governor Adelbert Ames advocated for appointing abolitionist and orator Frederick Douglass to the presidency. Positioning Douglass as a best representative of the African American race, he wrote, “I regard Mr. Douglas [sic] as more capable of doing good for his race….”[6] Ames framed Douglass as a “respectable” member of the African American race who was therefore best suited for the presidency. As Scholar Hakeem Jefferson describes, “those who embrace respectability politics believe that white Americans will reward group members’ good behavior; consequently, the lot of the group will improve.” Consequently, those proponents of respectability politics penalized those who failed to “do good for their race” and failed to live up to white standards.[7] White proponents cast men like Douglass or Revels as paragons of virtue, or the best models for freed people to follow, as they faced continuous discrimination from white America, but balancing the opinions of white and Black Americans was complex. In fact, Revels was dismissed from his position at Alcorn due to his opposition to Mississippi Governor Adelbert Ames’ reelection in 1874. White Americans likewise viewed Revels as a model for the African American race, which in their view, included not opposing the white male status quo. This allowed elite white Americans manipulate Black respectability politics for their own ends in the nineteenth century.

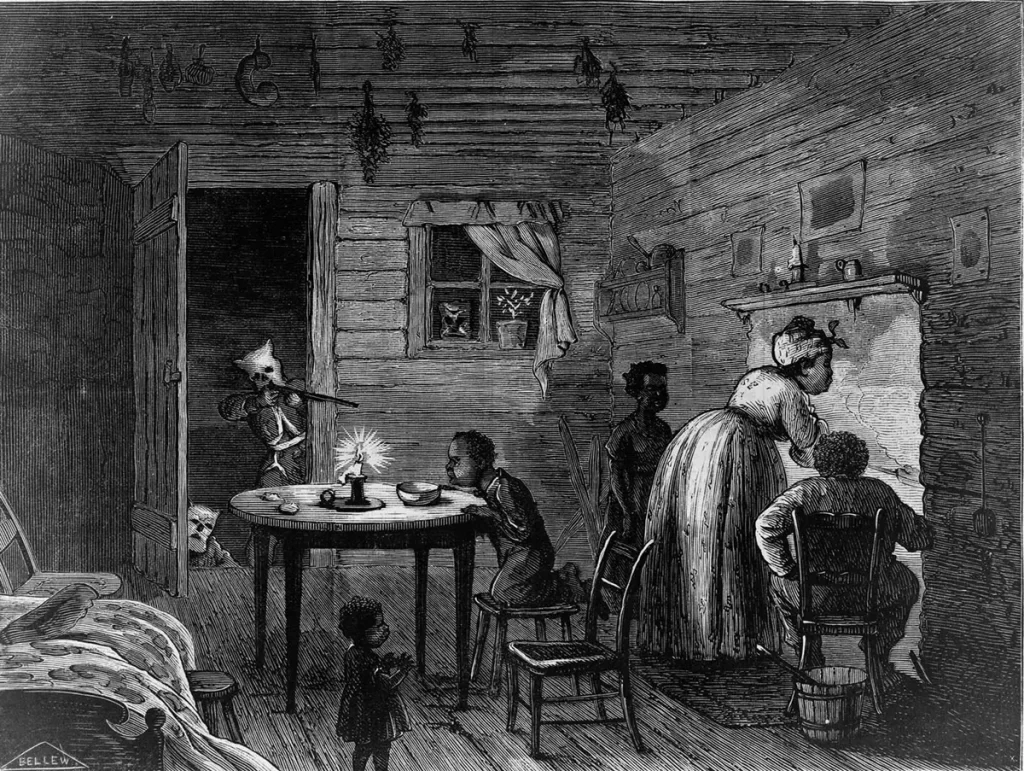

White citizens and lawmakers challenged the ideology behind respectability politics, but it also allowed spaces for interracial cooperation. Some white legislators wanted African Americans to achieve limited success and envisioned a small percentage becoming the leaders of their race. Others believed that education, which was key to African American success, should be limited or entirely unavailable to Black students. Educated African American men and women threatened the social, political, and economic infrastructure of the United States, wherein white supremacy was the norm. Furthermore, some believed the presence of African American students in schools threatened finite educational opportunities for white students. In a September 1873 issue of the Daily Mississippian, one author discusses the “practical monopoly” that “colored people” held over education. They theorized, “the university had, until now, prevented the attempt at a mixing of the white and blacks which must destroy any instruction of learning by forcing out the best classes of white students.”[8] Black students’ very presence in schools allegedly detracted from the experience and learning quality of white students.

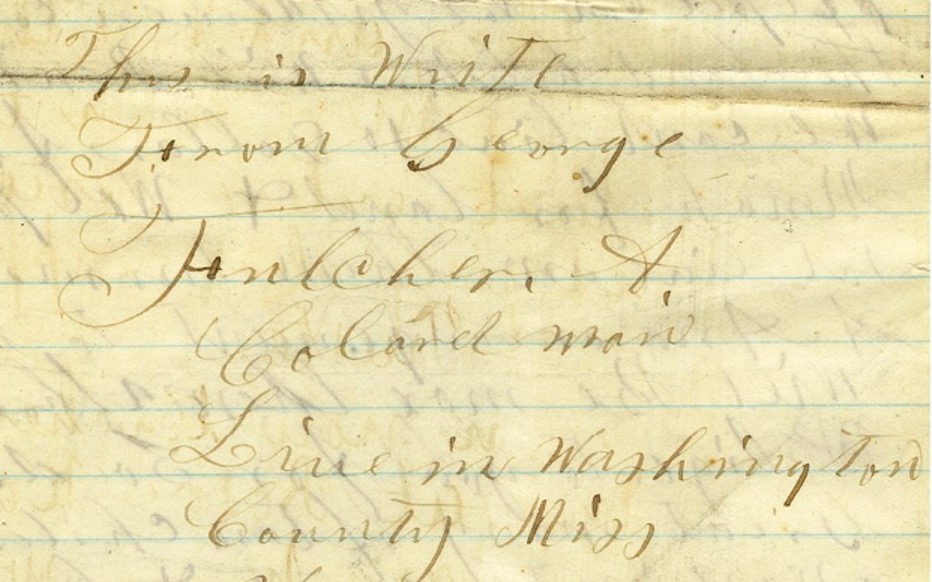

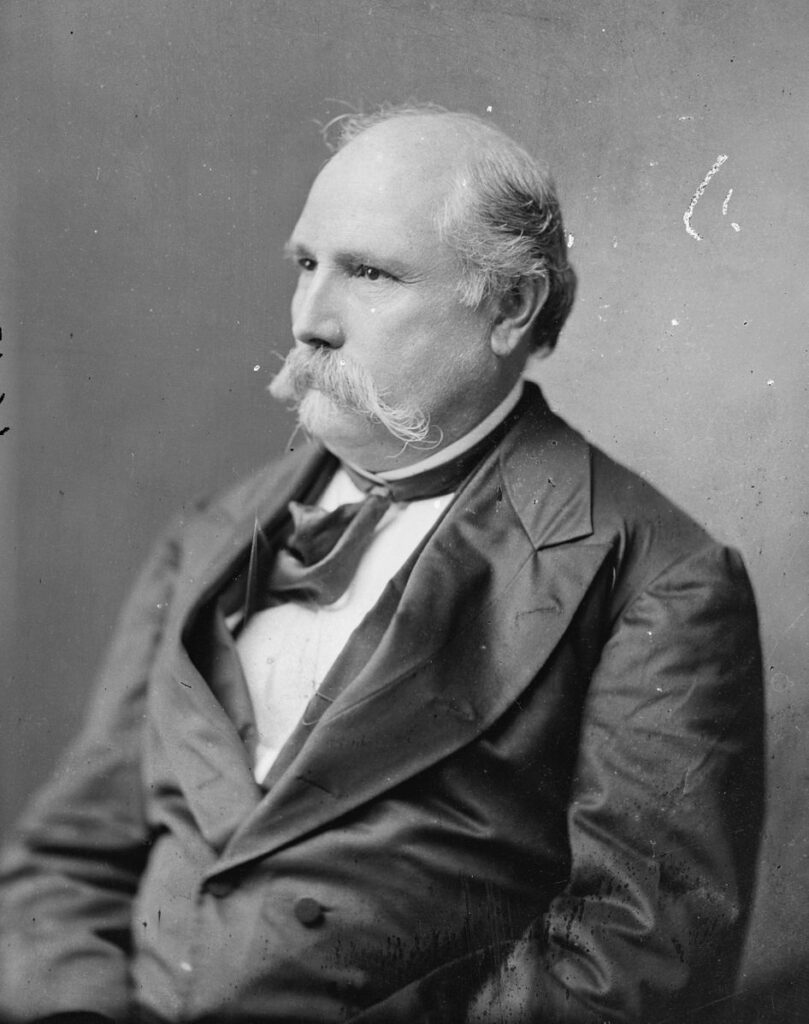

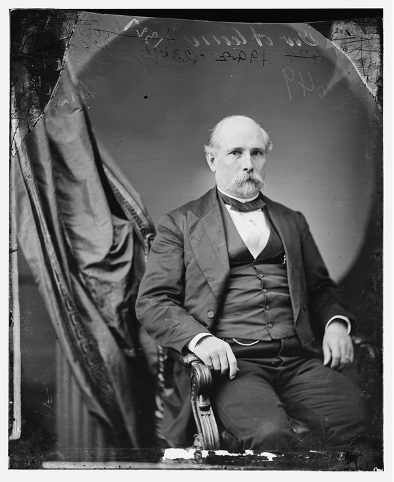

Six years into Reconstruction, Mississippi governor James L. Alcorn presented his radical stance on partially integrating African Americans into some higher education institutions, namely the University of Mississippi in Oxford, in an 1871 letter to the Mississippi Legislature. Governor Alcorn’s background was complex. He was a former enslaver and a Whig, but he was even denied a promotion due during his military service due to his growing anti-slavery political beliefs. Following the Civil War, he joined the Republican party and a growing body of other Republicans in the Mississippi Legislature who opposed formed Confederate President Jefferson Davis. After the war, Alcorn became an advocate of limited African American civil rights, including the right to vote and hold civil service positions.[9] In a letter to then-governor Ridgley C. Powers in April 1873, he called for Caroll Kelly, an African American man, to be pardoned and released from prison. He stated that he is “exercising the constitutional prerogative on behalf of the colored citizen of this country,” and that he thought that the African American “community” would be relieved at his release.[10] Kelly was pardoned eight days later.

In a letter to Congress, Governor Alcorn outlined a series of actionables, beginning with the expansion of university acceptance to include “the colored boy.” He wrote, “We ought not to be unprepared to discharge our obligations to the colored boy as we discharge it to white boys.”[11] Alcorn also requested the legislature put aside funding for African American education and scholarships that were previously only offered to poor white youth. For African American men, these awards would be given after they have completed four or five years of secondary schooling. Unfortunately, by 1867, funding for these scholarships would diminish from $50,000 in 1871 to $5,500 dollars in 1876 after Mississippi Democrats retook the majority in the state legislature. These financial scholarships, however, were built on an equality framework, not an equitable one: he would give both poor whites and African American men of any class the same treatment under the eyes of the university.

A clear proponent of public education, Alcorn supported racially integrating the University of Mississippi in 1870 and helped establish the land-grant for Alcorn University in 1871. Within five years of its conception, however, Alcorn University (which was then under the authority of Hiram H. Revels) was under duress. According to Judge J. Tarbell, in a letter reporting the state-of-affairs of the university to Governor Adelbert Ames, there was a chaotic atmosphere of “mutiny” and a corrupt board of trustees. He also frequently described the student body, composed entirely of African American students, as unruly and undeserving. Tarbell described “colored boys” who “receive[d]… certificates for wood they did not cut.”[12] Because of the allegedly poor management of the University, he alleged the African American male students would not be deserving of their college degrees. However, Tarbell seemed to advocate for the improvement of the University and the establishment of a new board but believed that the government should take authority over its affairs to ensure a successful future for the university and its African American students.

Alcorn made a complex comment one letter to Congress relating to language surrounding African American education, which was a subtle yet impactful departure from how men like Tarbell viewed their role in education: “By the time at which [African Americans] shall have made their coming demand for a collegiate education.” Note that Alcorn says that they “demand” collegiate education.[13] White Americans viewed higher education not as a right but a privilege to be earned, but it also highlights African Americans’ commitment to securing educational opportunities. Alcorn’s status as a former enslaver is not forgotten by historians because of his contributions to the early civil rights movements. However, his nuanced advocacy in Mississippi state Congress was an important historical event in land-granting for predominately African American educational institutions. At the same time, these “demands” Alcorn cited were a quick glimpse into the greater movement that African Americans headed and what they would achieve in the coming years.

Underlying these governmental decisions during Reconstruction was the notion that until African Americans reached the intellectual capacity of affluent white men, treating them as an inferior race was acceptable if not encouraged. Personally, I disagree both with this idea and the approach of just equality in education as men like Alcorn believed to be the extent of progress. Education is a specific necessity for African Americans of all genders and classes to tell stories of their joy, pain, and triumph—equitable education would achieve this. As Black Americans recognized during Reconstruction, equitable education includes the creation of HBCUs, because it is a necessity to be independent of white American institutions, including all-white schools that already exist, and define success for themselves. Most white male Americans had these rights to self-conception at the same time African Americans were being denied them.

Furthermore, I believe giving marginalized groups the power to decide how to exercise autonomy in education is the only way for that autonomy to come into fruition. Racially integrated and race-conscious education is the most effective way to create an America where multiple perspectives were represented. In 1867 during a speech to his fellow senators in Charleston, U.S. Senator Charles Sumner said, “A republic without education is like the creature of imagination, a human being without a soul, living and moving blindly, with no sense of the present or the future.”[14] Sumner continued on to say that, in order for southern states to reassociate with the Union, they must champion “public schools which shall be open to all without distinction of race or color, … and the new governments find support in the intelligence of the people.” Sumner, like Alcorn, adhered to equality instead of equity. Instead of creating schools specifically for African American students, such as HBCUs, previously existing schools should simply be colorblind—or ignorant of race and ethnicity—and accept all students. It seems that white men such as he and Alcorn, who advocated for more African American rights after Emancipation, acknowledged that there needed to be some reform, but could not or would not go as far as to specify why that reform needed to be focalized—or, why within formerly-segregated schools, there needed to be resources for African American students to go to that white students may not have ever needed.

Southern states and their civil servants needed to acknowledge the necessity of African Americans in education. The Radical Republicans believed an entirely new order needed to be created in the United States as African Americans demanded human rights and specific treatment after the legal end of slavery, which modern scholars would consider “equity,” not equality.[15] This new order would prioritize African Americans voicing their experiences and the experiences of others that continue to face oppression.

Alessandra Diaz is a high school senior in Queens, New York. She has been working at the Civil War and Reconstruction Governors of Mississippi Project as a research intern on the transcription and subject tagging research team since September of 2023, and intends to study History and Political Science at Columbia University beginning in the fall of 2024.

[1] James D. Anderson, “Philanthropy, the State and the Development of Historically Black Public Colleges: The Case of Mississippi,” (Minerva 35, no. 3, 1997), 295–309.

[2] M. Christopher Brown and James Earl Davis, “The Historically Black College as Social Contract, Social Capital, and Social Equalizer,” ((Peabody Journal of Education 76, no. 1, 2001), 31–49.

[3] Office of History and Preservation Office of the Clerk, U.S. House of Representatives, “Former Members: Hiram Rhodes Revels, 1827–1901” in Black Americans in Congress 1870–2007 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2008), 56.

[4] Clara Merritt DeBoer, His Truth Is Marching On: African Americans Who Taught the Freedmen for the American Missionary Association, 1861-1877. (Routledge, 2018), 1995

[5] See Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, Righteous Discontent: The Women’s Movement in the Black Baptist Church, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993), 188.

[6] Mississippi Governor Adelbert Ames to F. C. Harris, (The Civil War and Reconstruction Governors of Mississippi Project), 1. https://cwrgm.org/item/mdah_803-992-06-04

5 Jefferson, Hakeem. “The Politics of Respectability and Black Americans’ Punitive Attitudes,” (American Political Science Review 117, no. 4, 2023), 1453.

6 Hazel V. Carby, Race Men (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998), 5.

[8] “The Rights of Freedmen,” The Daily Mississippian, September 14, 1865.

[9] David Sansing, “James Lusk Alcorn: Twenty-eighth Governor of Mississippi: March 1870 to November 1871,” Mississippi History Now. Mississippi Historical Society, December 2003. https://www.mshistorynow.mdah.ms.gov/issue/james-lusk-alcorn-twenty-eighth-governor-of-mississippi-march-1870-to-november-1871

[10] James L. Alcorn to Mississippi Governor Ridgley C. Powers, April 10, 1873, (The Civil War and Reconstruction Governors of Mississippi Project) 1. https://cdm17313.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/mdah/id/36611

[11] James L. Alcorn to Mississippi Legislature, May 1, 1871, (The Civil War and Reconstruction Governors of Mississippi), 4. https://cdm17313.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/mdah/id/25639

[12] Judge J. Tarbell to Mississippi Governor Adelbert Ames, December 25, 1875, (The Civil War and Reconstruction Governors of Mississippi Project), 6. https://cdm17313.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/mdah/id/33268

[13] James L. Alcorn to Mississippi Legislature (The Civil War and Reconstruction Governors of Mississippi Project), 5. https://cdm17313.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/mdah/id/25639

[14] Tyack, David, and Robert Lowe. “The Constitutional Moment: Reconstruction and Black Education in the South.” (American Journal of Education 94, no. 2 , 1986), 237.

[15] Richard White, The Republic for Which is Stands (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), 366–67.