By Lucas Somers, Ph.D. , Asst. Prof. of History, Lindsey Wilson College

Last time, we looked at Mississippi Governor James Lusk Alcorn’s formation of a state Secret Service Bureau to combat the Ku Klux Klan in 1870. That agency sent U.S. veteran and former deputy sheriff John J. Gainey on an undercover operation to determine the identities of individuals responsible for violence against African Americans in Lafayette County. He successfully infiltrated the local KKK chapter, gained the trust of one of its members, and organized a confession witnessed by local officials.

Gainey arrived in the county seat of Oxford on July 19, 1870, but his presence in town did not remain a secret for long. The Oxford Falcon, a Democratic newspaper, even alerted their readers that “One of Alcorn’s secret detectives was in town this week.”[1] While in Oxford and before going undercover, Gainey coordinated his investigation with three civil officers: C. N. Wilson, Edwin M. Main, and W. H. Ford. Each of these men received appointments in 1869 from the previous Republican Governor Adelbert Ames—who had been himself been appointed by the U.S. Congress—which earned each of them the ire of Democratic observers even before taking their respective offices.[2] Despite Alcorn’s hope that the Secret Service would thwart Klan violence and keep the federal government at bay, many white residents of Lafayette County perceived the individuals carrying out the state’s work as vehicles of Radical Reconstruction. Nevertheless, those officials proved useful to Gainey’s investigation. Wilson provided him with information about potential persons of interest, which led Gainey to visit the plantation of Thomas Woods, located roughly fourteen miles outside of town. Gainey quickly befriended Woods’s twenty-year-old son, Ignatius “Few” Woods, and Gainey soon met other members of the local Klan as well. Few Woods even bragged to his new acquaintance that the Lafayette County chapter of the KKK had been personally organized by Nathan Bedford Forrest in April 1867. After feigning interest in their organization and earning their trust for about a week, Woods and his fellow Klan members invited Gainey to be initiated into their ranks.

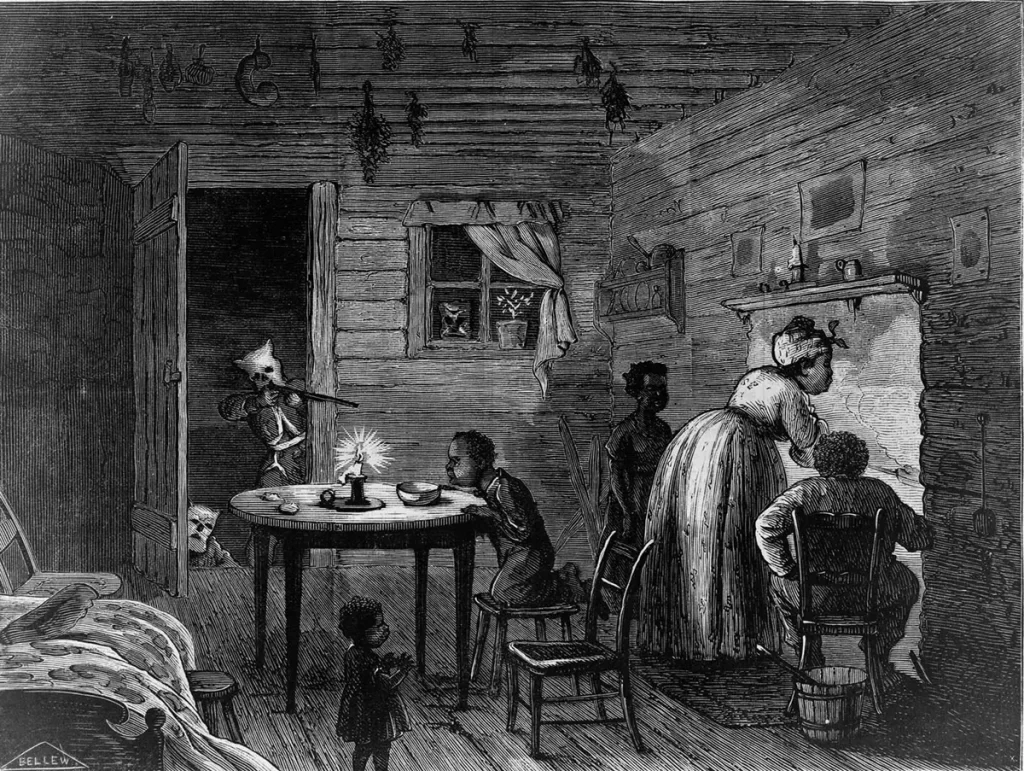

Courtesy Library of Congress.

The story reached its climax when Gainey and Few Woods went into Oxford together one evening. After convincing his new friend to purchase some wine in town, the undercover agent secretly met with two of his local contacts, Wilson and a former sheriff named Mahon. Gainey’s plan involved coaxing Woods into recounting KKK crimes by “plying with the bottle,” while he arranged for the two civil officers to hide below them under a bridge so they could overhear the confession.[3] This plan worked to perfection as Woods revealed the names of several masked Klansmen responsible for multiple shootings of freed people in that county. Gainey then reported their identities to the Secret Service headquarters and local officers learned this crucial information as well.

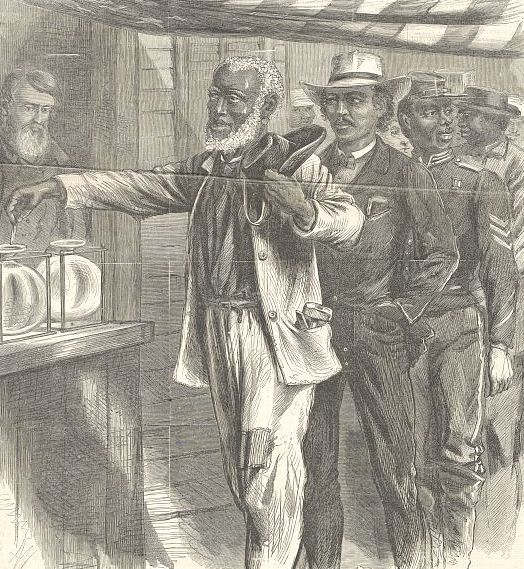

Now, the particular attacks that were retold in the confession took place at the home of a “Widow Watson,” where KKK members John Conkle, Mat Goolsby, Few Woods, and others attacked an African-American man and shot him in “the back with a double barreled shot gun, forty-seven buck shot entering into him.”[4] Gainey may be describing the shooting of a freedman named Jacob Watson who lived next door to a widowed white woman named Amanda M. Watson in 1870. He was a captain in a Black militia company and led a local Union League chapter at that time as well.[5] According to other sources, earlier that year the Lafayette County Klan made a series of raids against Jacob Watson and his lieutenants, Sandy Newberry and Jake Boone, after their militia company conducted nighttime drills that “annoyed” whites in the vicinity.[6] Those sources reported that Jacob Watson received serious gunshot wounds from those Klan raids, suggesting that Woods’s confession to Gainey was describing this same attack from a few months prior.[7] Throughout the South during Reconstruction, the KKK specifically targeted Black men belonging to Union Leagues—which were local organizations designed to politically mobilize Black voters—and militias in large numbers in order to intimidate their efforts toward racial equality. African Americans continually struggled to protect their political rights and their own lives, though their allies within the state and federal government dwindled significantly by the end of the decade.

Courtesy Library of Congress.

The existing records do not indicate that Gainey’s investigation led to any legal action against Watson’s attackers. During its brief existence, Mississippi’s Secret Service stretched itself thin attempting to investigate Klan attacks throughout the state, and it seemingly lacked sufficient resources to curtail the violence in a meaningful way. With a staff of only seven detectives, the agency had little hope of combatting the vigilantes when many whites either supported or tolerated them.[8] In fact, Gainey observed during his mission, “Almost every young man in the county is a member of the organization or in sympathy with those who are in it.” This case shows that while Alcorn’s Secret Service could identify and expose those responsible for Klan violence, their ability to protect Mississippi’s Black communities proved negligible.

Alcorn’s hope of defeating the Klan with his Secret Service Bureau ultimately failed to gain an upper hand on the pervasive white terrorism throughout the state. As Reconstruction fell apart in the mid-1870s, the Democratic Party regained control of the Mississippi government, curtailed the political rights of African Americans, and ushered in the Jim Crow era by the end of the century. Beyond a dramatic story, Gainey’s letter offers insight into that the brief period during Reconstruction when the state government had the opportunity to protect the rights and the lives of African Americans. But that would have required more than “cautious and irresolute” action from leaders like Alcorn to be successful and permanent.[9]

Lucas Somers is Assistant Professor of History at Lindsey Wilson College. He earned his Ph.D. at the University of Southern Mississippi in May 2022. His dissertation is entitled Embattled Learning: Education and Emancipation in the Post-Civil War Upper South. In 2018, Lucas served as a Graduate Research Associate for the Civil War Governors of Kentucky Digital Documentary Edition and was a research assistant for the Civil War & Reconstruction Governors of Mississippi project in the summers of 2020 and 2021. He also served as USM’s McCain Graduate Fellow in 2021-2022.

[1] Editorial, The Oxford Falcon, July 23, 1870.

[2] “Officials for Lafayette County,” The Oxford Falcon, June 26, 1869; “Blood Money. Clayton’s Thieves and Murderers Receiving the Reward of Their Infamy. A Nice Party to Control the Affairs of a County,” The Oxford Falcon, November 27, 1869.

[3] CWRGM has not been able to find a Sheriff Mahon in Lafayette County between 1850-1870.

[4] According to a later account of one of the Lafayette County Klansmen, B. F. Goolsby, Mat Goolsby’s father, served as the Grand Cyclops of that den of the Klan, Julia Kendel, “Reconstruction in Lafayette County,” Publications of the Mississippi Historical Society 13 (1913), 240-241.

[5] 1870 United States Federal Census [database online], (Provo, Utah: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2009).

[6] “The Shooting Affair at Near Mrs. Simmons’,” The Oxford Falcon, April 2, 1870.

[7] Kendel, “Reconstruction,” 240-241.

[8] William T. Blain, “Challenge to the Lawless: The Mississippi Secret Service, 1870-1871,” The Mississippi Quarterly 3, no. 2 (Spring 1978), 231.

[9] Michael Perman, The Road to Redemption: Southern Politics, 1869-1879 (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1984), 35.