By: Michael Singleton, Former CWRGM Assistant Editor

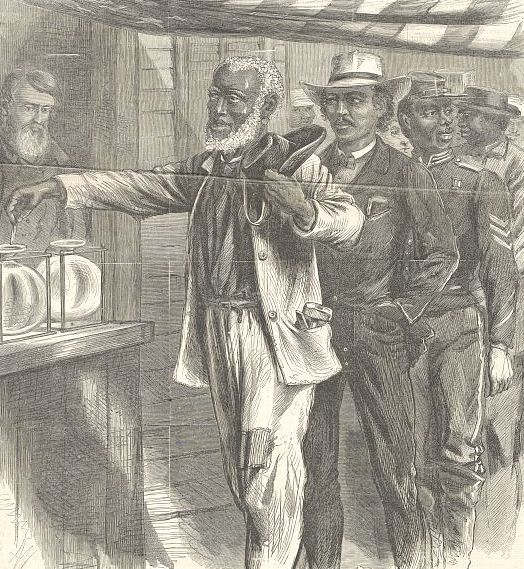

In the last post, I relayed several of the unique documents from the CWRGM collection that featured proposals sent by civilians to Mississippi Governor John Pettus on how best to fortify and defend the Mississippi River. While notable for their detail and designs, those propositions primarily focused on conventional techniques like land-based fortifications and a network of river obstructions. Today’s post highlights a series of letters from 1862 that offered a plan for an unconventional naval weapon that the author believed would neutralize the power of the United States Navy. Like the previous documents, these proposals contain a fascinating drawing accompanying the written proposal. Similarly, it also appears to have gone unimplemented at the state and national levels for untold reasons. Regardless, these documents contain a range of innovative, technical, and scientific thinking that—even if disregarded by government authorities— further demonstrate the extent to which some enterprising civilians sought to support and influence the Confederate war effort with their own advice and insight.

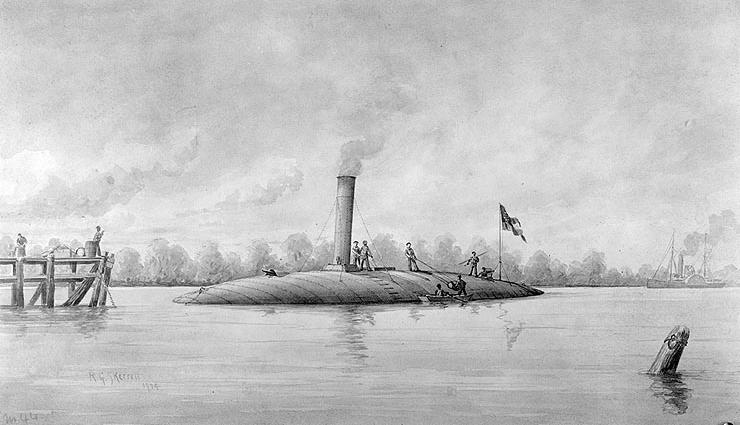

On July 29, 1862, William R. Scott of Wilmington, North Carolina, sent a letter to Governor Pettus detailing his plans for a “Steam Battering Ram” that he felt would allow the Confederate Navy to “Destroy the Federal Navy that is in the Miss River” and thus “win and Rule their own rights.” Scott’s proposal envisioned an ironclad ship adapted from the hull and boilers of an existing steamboat. The crux of his design was a steam-powered, multi-use battering ram that he asserted could deliver repeated blows below the waterline on an enemy ship. Scott suggested that the state of Mississippi complete the construction at the shipyard on the Yazoo River and likened its armored design to that of the famed CSS Arkansas that had only weeks before been completed.[1] In total, Scott’s first letter was long on rhetoric and short on technical details. He provided no specifics on how the ram would operate, nor details on its prospective dimensions, crew, armament, or necessary construction material. In this initial proposition, all Scott provided was his brief proposal, a rough sketch (that is missing), and an assessment conducted by officials from the Confederate Navy Department that endorsed his design.

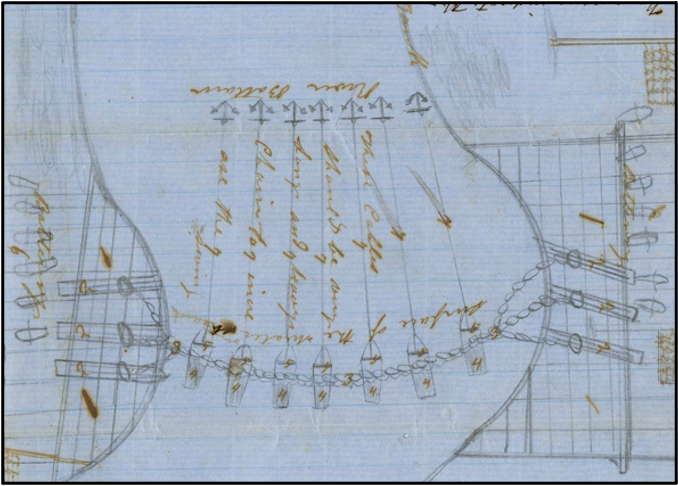

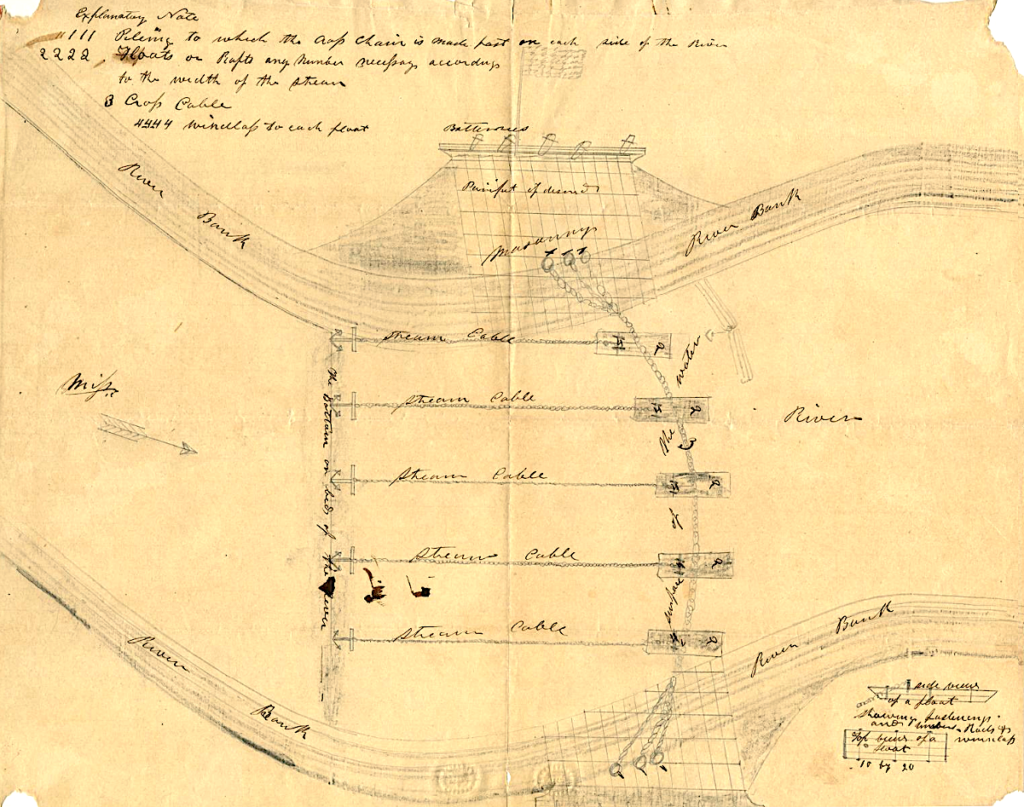

It is clear that Pettus did not answer Scott’s initial letter because, in December 1862, he again petitioned the Governor and stated that “not having heard from you concerning it” he would “take the liberty to send you another sketch.” Scott’s second letter is of greater significance as he included a detailed sketch of the boat and an eight-page copy of the meeting minutes from a sub-commission of the South Carolina government that inspected and approved the plans. Scott’s design (Fig. 2) shows a double-acting steam engine mounted towards the boat’s bow that would operate a “battering ram” protruding below the waterline. He asserted that this weapon could be “driven with a force of from one hundred to six hundred tons depending on the size of the engine” and could do so against an enemy ship at a rapid pace of up to twenty blows per minute.

In essence, Scott envisioned a vessel that would, like a boxer, close with a Federal ship and deliver repeated body blows until its hull was breached or the craft fled. Such a design differed widely from the operation of conventional naval rams like the CSS Virginia and the CSS Tennessee, which both depended on the force of the ship’s momentum to deliver a blow and relied on mounted artillery for defense and offensive capabilities.[2] Contrarily, Scott’s ship would be purely offensive in nature as it evidently (according to the basic design) featured no other form of armament beyond the steam ram. This decision would mean that the ship would have relied solely on the reliability of its steam engines to generate sufficient speed and its ability to get close to enemy ships to be effective. The design further meant that the ship would have no other defensive capabilities than its ability to close with and batter enemy vessels.

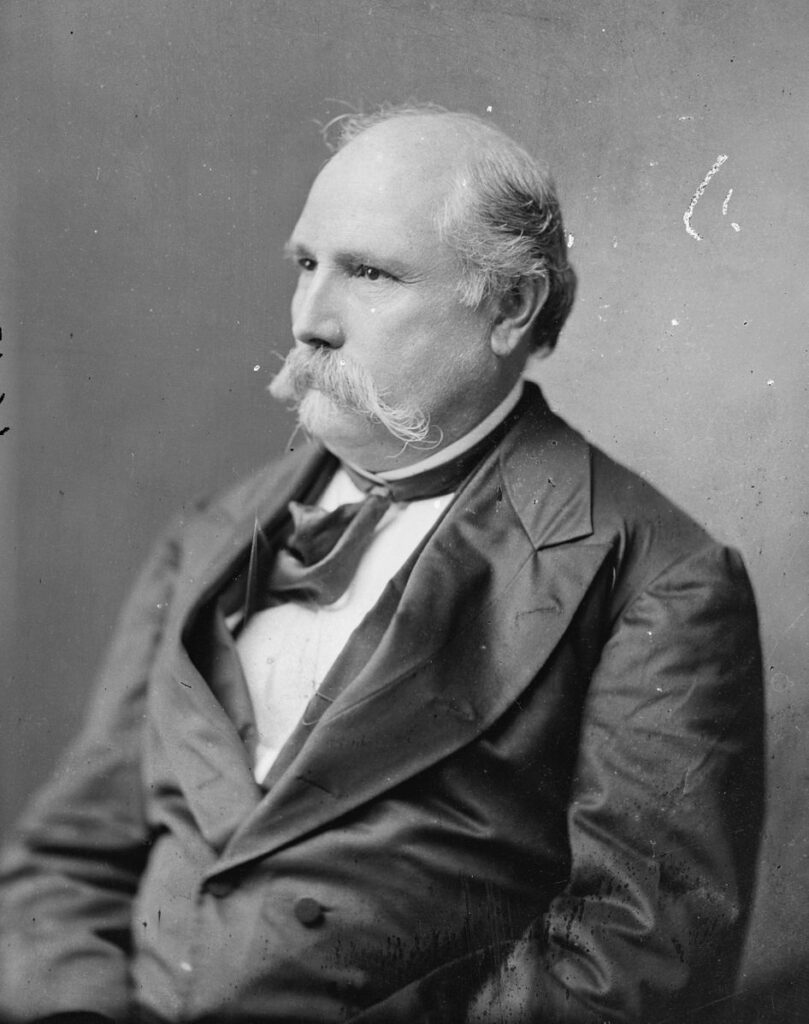

Nevertheless, more than any other innovative proposal in the CWRGM collection, Scott’s design appears to have come the closest to fulfillment. This fact is evident from the South Carolina commission report, which included copies of correspondence between Scott and numerous high-level Confederate officials who each expressed support for his design. For example, Confederate Lieutenant General P. G. T. Beauregard endorsed the plan in October 1862 by stating that he thought “favorably of the proposed battering Ram of Mr. W. R. Scott” because it could “continue the battering process without having to back for a new momentum.” Moreover, the South Carolina commission unanimously approved the plan and recommended its immediate implementation, while some Confederate Naval Department officials like its Chief Engineer William P. Williamson likewise endorsed the proposal and recommended it for action. Finally, Scott’s plan even reached the desk of Confederate President Jefferson Davis in September 1862, whose secretary (and son of Robert E. Lee) Colonel George Washington Custis Lee promised to refer the plan to the Secretary of the Navy, Stephen F. Mallory.

Likely, Scott’s plan went no further than Mallory’s (or Pettus’) desk, for no such ironclad was ever constructed in total in Mississippi or elsewhere. This is possibly because of the failure of the singular ram CSS Manassas in combat in 1861 or that it violated Mallory’s policy to both offensive and defensively capable ironclads.[3] However, it is possible that Scott’s plan did influence the construction of the CSS Charleston, which was constructed by the state of South Carolina in the fall of 1862 and that interestingly featured a unique iron ram protruding at length from its bow.[4] This is a feature not seen any other Confederate ironclads and, given the South Carolina commission’s enthusiasm and recommendation for his proposal, could mean that they incorporated the spirit of Scott’s design rather than it completely. In any event, despite his evident passion and persistence, William Scott’s idea went unfulfilled as it applied to the state of Mississippi as Pettus, and local Confederates forged ahead with more conventional plans on the Mississippi River. In a third and final post, we will move below the waves to detail another unconventional proposal broached to Governor Pettus about thwarting the Federal Navy along the Mississippi River. Stay tuned!

Michael Singleton was the CWRGM Assistant Editor from 2021-2022. He earned his M.A. in History from the University of Southern Mississippi in August 2022 and his B.A. in History from the Virginia Military Institute in 2013. While a student at USM, Michael served as a Public History intern on the CWRGM project in the summer of 2021 and a graduate teaching assistant from 2020-2021. He also served as an active duty Infantry officer in the U.S. Army from 2013 to 2020.

[1] The CSS Arkansas was a large ironclad completed at a shipyard located on the Yazoo River in Mississippi in the mid-summer of 1862. It featured railroad iron for armor and two large (but unreliable) steam engines for propulsion. It left the shipyard on July 14, 1862 to engage Federal ships on the Mississippi River. In a series of engagements, it ran the Federal fleet above Vicksburg and remained near that city until it travelled south to participate in a Confederate offensive to retake Baton Rouge, LA. In that action, it suffered debilitating engine trouble and was abandoned and scuttled under fire by its crew. See, Saxon Bisbee, Engines of Rebellion: Confederate Ironclads and Steam Engineering in the American Civil War (Tuscaloosa, AL: The University of Alabama Press, 2018), 68-81.

[2] Bisbee, Engines of Rebellion, 7, 230.

[3] Bisbee, Engines of Rebellion, 8, 33, 37, 84.

[4] Bisbee, Engines of Rebellion, 132-133.