By: Michael Singleton, former CWRGM Assistant Editor

As should be clear to anyone who has explored the documents in the CWRGM collection, nineteenth-century individuals wrote to their governors about virtually everything. Whether they were requests for criminal pardons, exemptions from military service, applications for employment, or appeals for mediation, white Mississippians had few qualms about penning a letter to their state executives. It shouldn’t be surprising then that this trend also carried over to the military sphere. Throughout the Civil War, a handful of Mississippi civilians took it on themselves to submit proposals to their Governors on how best to fight the Federal army and navy. In many of these cases, recommendations revolved around defending Mississippi’s many waterways, especially the Mississippi River. While small in number, these letters comprise some of the collection’s most interesting and visually entertaining documents because they often include detailed drawings and descriptions of the author’s plans. Military history buffs will especially enjoy the documents that relay designs for new military equipment meant to revolutionize the Confederate war effort.

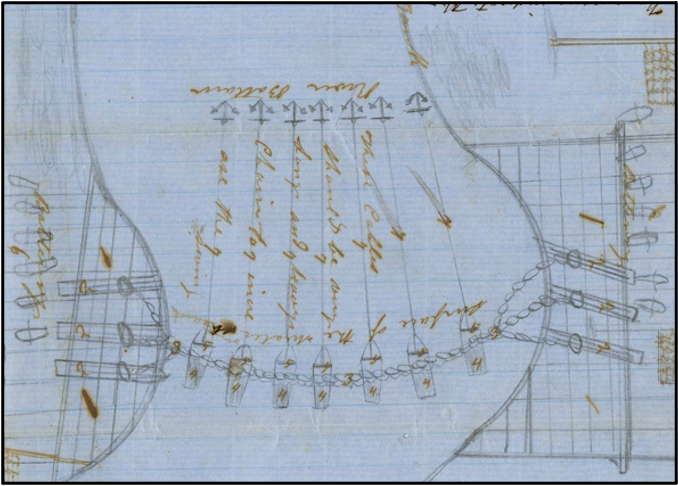

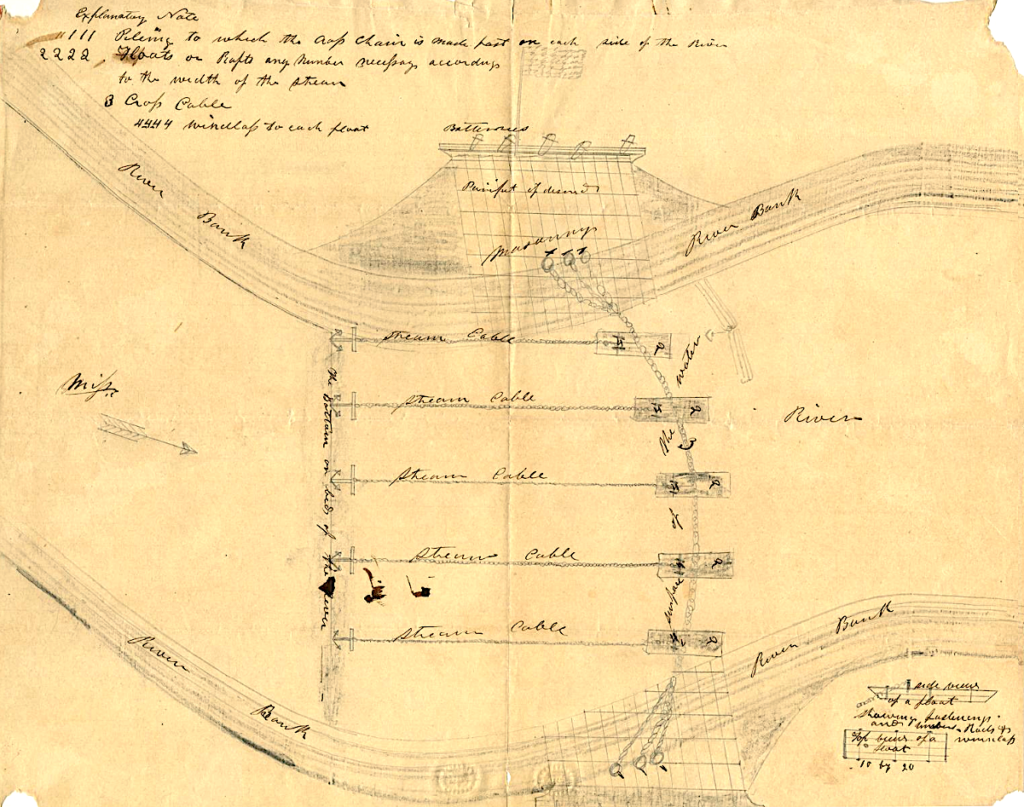

A series of letters from an Edward Rew in Sageville, Mississippi, are perhaps the two best examples of this phenomenon. Before the war, Rew was a moderately successful carpenter turned planter in Lauderdale County with no evident engineering or military experience.[1] Nevertheless, in August 1861, he wrote Mississippi Governor John J. Pettus a lengthy plan to “aid in the defences of the Mississippi River,” which he felt, if implemented, would make “an effectual barrier to the enemy should they attempt to send a fleet down said river at this or any future time during the present war.” Accompanying Rew’s letter is a detailed drawing depicting the various elements of his defensive plan.

Rew proposed that the state build a large iron chain to stretch across the Mississippi River. This obstacle would be secured at both ends by timer pilings driven into the riverbank, while a series of wooden boats with anchors would be scattered along the chain to hold it in place. He also proposed that Confederates place other obstructions upstream of the chain “so as to deaden the headway” of boat traffic and allow fortified artillery batteries on both riverbanks to bombard and sink any Federal ships. At his own admission, Rew submitted a similar—albeit less-detailed—plan to then Confederate Secretary of War Leroy Walker to possibly attract his attention.

It is unclear how (or even if) Governor Pettus responded to Rew’s first suggestion, but it is fair to think that the governor likely shelved the idea and moved on to more practical concerns. Nevertheless, six months later, in February 1862, Rew resubmitted his plan to Pettus—this time apparently at the governor’s request. In this letter, Rew referenced the need to save the Confederacy from “any more Ft. Henrys and Donnalsons,” so it is possible that those twin defeats only weeks before sparked a renewed desire to improve Confederate defenses along the Mississippi. Rew’s second proposal differed little from his first, though he did add the possibility of employing “submarine batteries” to supplement the chain obstacle. Although Rew admitted that such devices “would hardly be necessary,” his reference to underwater mines alluded to the tactics Confederates would employ in great numbers later in the war. His dismissal of these mines—while later proven to be misguided—nonetheless demonstrated a striking familiarity with up-and-coming military technology for an untrained civilian.

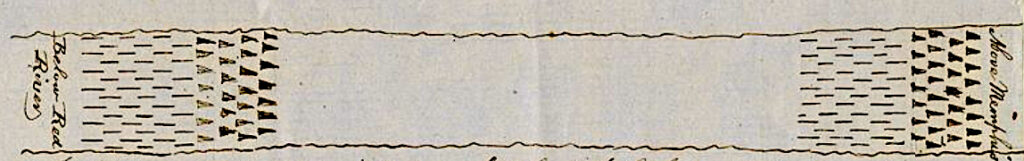

In July 1862, just six months after Rew’s letters, R. P. Guyard of Bogue Chitto, Mississippi, wrote Governor Pettus to provide “some suggestions that can permanently secure for all time…as much of the Mississippi River as is indispensable to have crossings for travellers, and railroads wherever possible.” Much like Rew, Guyard proposed that state or Confederate authorities obstruct the river by placing obstacles directly in its flow, though he differed on how it should be done. “Chains or cables across the river as a barrier is worse than useless,” he claimed.

Instead, Guyard recommended that teams of workers (likely enslaved people) use a specially-fitted steam engine to drive sharpened poles into the river bottom to create a dense field of obstacles. A secondary group of triangular wooden piers would follow the main obstacle to further slow movement. Like Rew, Guyard envisioned that fortified artillery batteries with sharpshooters would overwatch the obstructions from the riverbank and attack Federal ships as they approached. This construction would occur in multiple locations on the river, with at least one obstacle belt placed north of Memphis, TN. At the same time, another would face southward “below the mouth of Red River” to prevent movement up from newly-occupied New Orleans, LA. No doubt reflecting the acknowledgment that war with the United States could drag on for some time, Guyard proposed that his proposed obstacles would “endure for ages” and permanently block traffic on the Mississippi.

In subsequent months, other civilian writers made similar pitches to Pettus about obstructing the river (such as one anonymous proposal from South Carolina or another from Hazlehurst, Mississippi). In any event, though, no such elaborate obstacles were ever constructed across the waterway in Mississippi. This choice was undoubtedly the result of the sheer impracticality of such an elaborate and challenging venture and because of the significant resources and labor it would have required.[2] Rather, Confederate defenses along the river relied on a combination of massed artillery at fortified points like Port Hudson, Louisiana, or Vicksburg, Mississippi, some minor obstructions, and a small force of naval vessels—including some ironclads. To the extent that Confederates employed techniques like those suggested above, they came at more remote locations along the smaller inland waterways like the Yazoo and Sunflower Rivers. There, Confederate troops sunk wooden obstructions and used artillery to overwatch for approaching Federal ships much like in Rew or Guyard’s proposals. They also employed “submarine batteries” or “torpedoes” to great effect—most notably in the sinking of the U.S.S. Cairo in December 1862.[3]

The efficacy of employing more unconventional devices like “torpedoes” was a point made to Governor Pettus in a December 1862 letter by one J. B. Poindexter, an officer in the Third Mississippi Infantry. Poindexter’s forward-looking vision would be matched by other proposals from citizens for more innovative solutions to the threat posed by the United States Navy.

The next blog post in this three-part series will detail these sometimes-radical suggestions. Stay tuned!

Michael Singleton was the CWRGM Assistant Editor from 2021-2022. He earned his M.A. in History from the University of Southern Mississippi in August 2022 and his B.A. in History from the Virginia Military Institute in 2013. While a student at USM, Michael served as a Public History intern on the CWRGM project in the summer of 2021 and a graduate teaching assistant from 2020-2021. He also served as an active duty Infantry officer in the U.S. Army from 2013 to 2020.

[1] U.S. Census Bureau, 1860 United States Federal Census, “Census Place: Beat 4, Lauderdale, Mississippi, Page: 371,” NARA, Publication M653, Ancestry.com. https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/38747111:7667.

[2] It should be noted, however, that Rew and Guyard’s plans had some basis of precedent. When Confederate forces occupied Columbus, Kentucky, in September 1861 they strung a large iron chain across the Mississippi River one mile above town. This chain was suspended below the waterline by a series of boats posted along its length. Numerous artillery batteries overlooked the obstacle from the high bluffs along the river. Reportedly, numerous “torpedoes” were also deployed along the chain and around the area. In almost every sense, this network of obstacles matched Edward Rew’s proposal to Governor Pettus in August 1861. See O.R. ser. I, vol. 7, pp. 436, 534; “Columbus-Belmont State Park—Historic Pocket Brochure Text,” Kentucky Department of Parks, https://parks.ky.gov/sites/default/files/listing_documents/bd5d0c09888351da895977a12981568a_Col-Belmontpcktbrochure.pdf.

[3] Neil Chatelain, Defending the Arteries of Rebellion: Confederate Naval Operations in the Mississippi River Valley, 1861-1865 (El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2020) 205-208, 246-250.