By Lindsey R. Peterson

Increasing quantities of data are being made available online, making it easier to lose sight of humanity in digital spaces. Therefore, it is essential for diverse groups of users — scholars, educators, archivists, librarians, students, and the public — to evaluate the quality of online resources. This often means critically assessing our data and its uses, including if the representation of the people in the collection and its data is equitable. Users should be asking whether the data produced by digital editions is replicating, amplifying, or challenging inequalities and stratifications in contemporary society. This post introduces users to an expansive (but not exhaustive) list of questions to ask of data in digital editions based on our own exploration of the data we are producing at the Civil War & Reconstruction Governors of Mississippi Project (CWRGM). Consequently, it is designed to aid educators invested in teaching data literacy and accompanies CWRGM’s “Exploring Data in Digital Editions” lesson plan. Fundamentally, it seeks to remind users of data’s human element.

USING DIGITAL EDITIONS

Digital editions produce massive amounts of data for scholarly, educational, and public use. Implicit within digital editions are concerns about equity. The Data Equity Framework is an online resource advocating for equity in data science. They note, “Data science methods can produce results, but only through interpretation can we garner any useful meaning from them.” Rather than being infallible, they remind us that processing data is subjective. They note, “It’s a combination of our best understanding of the limitations of the data, the methodology, and the content.” Data, however, often seems objective. Therefore, issues of equitable data are even more critical, as users mistakenly equate data with fact. This can lead users to overlook the need to evaluate online resources. While this post is specifically about documentary editions, the digital humanities seek to help users uncover and explore the subjective nature of data.

The following questions are designed to push users to analyze: Whose voices are represented in these collections and how? Whose voices are absent and why? It is imperative for users to critically evaluate the data produced by digital editions. Throughout this post, I offer several questions to help users do just that by providing examples from CWRGM where I work as the project’s co-director alongside Dr. Susannah J. Ural.

These key questions of analysis are designed to assist users who want to evaluate online resources. Specifically, I will review the data created by CWRGM, paying particular attention to equity and representation. But I also reflect on open access, digital accessibility, and usability. These questions can serve as a guide for facilitating discussions about data literacy, the humanities, and digital editions in the K-12 and post-secondary classroom. CWRGM even offers a 12th grade lesson plan at the website to help users do just that, which users can find here.

KEY QUESTIONS TO EVALUATE ONLINE RESOURCES:

- What kinds of qualitative and quantitative data does the project produce and how is it generated and maintained?

- For example, is it by metadata, indexing, transcriptions, images, mapping/GIS coordinates, annotation, or something else?

- Is it open? What programs generate the data and how is it created?

- How does the edition’s data impact how people use the edition and what they know about the subjects/people contained in the collection?

- How are people represented by the data?

- For example, is it by a marker on a map, name, a group identity, or something else?

- How does this representation shape what can be learned about the subjects/people in the collection?

- What are the potential limitations and/or dangers of these representations or lack of representations?

- How can the digital edition address or subvert these possible limitations?

- How can users’ work—such as annotation, research, or art—address or subvert these possible limitations?

- While these questions are useful in the abstract, diving into the data found within CWRGM demonstrates how these ideas and inquiries can be framed when looking at a specific digital edition. I also offer examples of potential issues and opportunities found within CWRGM’s data.

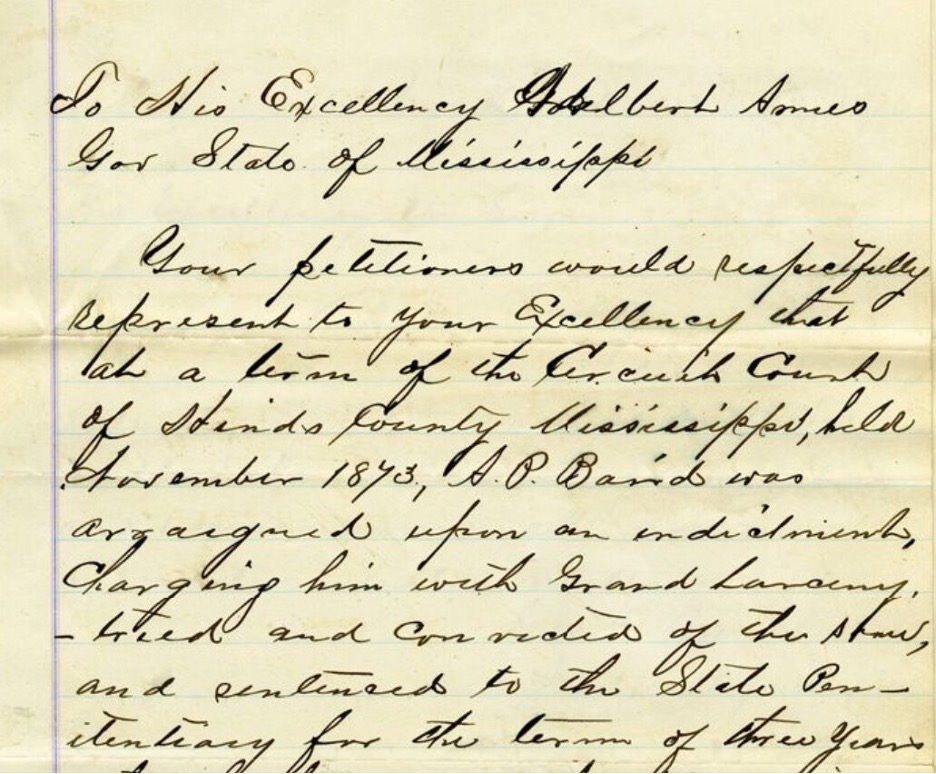

Petition to Mississippi Governor Adelbert Ames; March 24, 1876. Courtesy of the Civil War & Reconstruction Governors of Mississippi. Click on image to view entire document and transcription.

WHAT IS CWRGM?

CWRGM is a digital edition that is digitizing 20,000 documents sent to the governors of Mississippi during the American Civil War and Reconstruction (1859–1882). Americans from all backgrounds wrote to the state’s governors with their concerns, and after 1865, this included African American authors. With NEH/NHPRC-funding, along with other support, these records are made freely available online. They include high-quality images of the original documents alongside transcriptions, which also feature annotated subject tags.

Document metadata, in-text subject tags, and annotations are designed to increase the discoverability of the people within the collection. They can help shine a light on historically marginalized people such as African Americans, women, and impoverished people. But the project also generates massive amounts of quantitative data for research and classroom use. New documents become available every few months until the project’s completion in 2030. The quantitative data is made freely available on the website and is updated every six months.

The documents housed at CWRGM provide an example of how to evaluate online resources. The methods our research team employs to increase discoverability within these collections create fruitful opportunities for users to think critically about how data is produced, the ethical implications of that data, and the data’s opportunities and its limitations. To explore these possibilities, I will refer to the African Americans subject tag and its cooccurrences file.

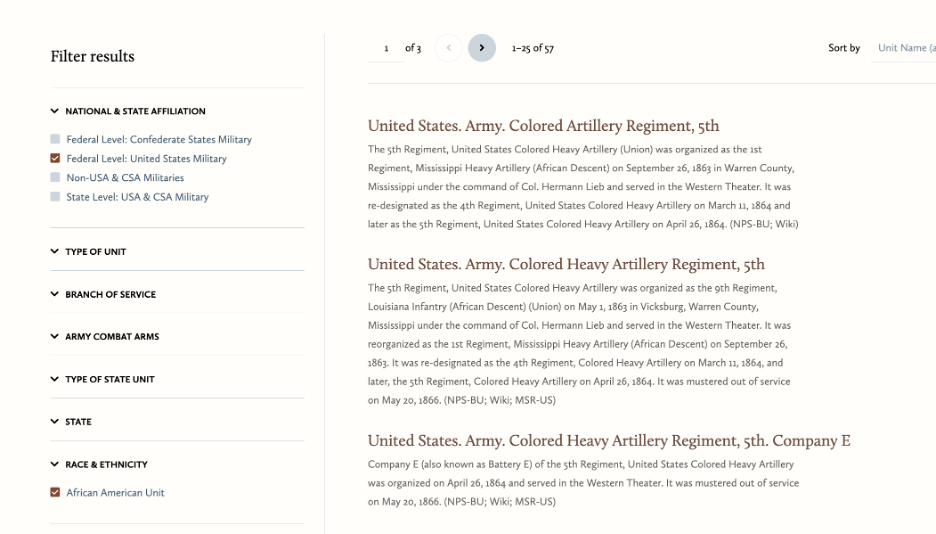

Screen capture of subject tags and facets under the Military Units category. Courtesy of the Civil War & Reconstruction Governors of Mississippi. Click on image to view all available military unit subject tags at CWRGM.

WHAT IS A CWRGM SUBJECT TAG?

When project researchers identify language that falls under one of CWRGM’s nine subject tag categories, they link it to an internally controlled vocabulary. For example, various references to enslaved people (such as servants, slave, servile population, etc.) are tagged with the controlled subject term “African Americans–Enslaved People.” A tag is added to a document no more than once. Then it generates an index of all documents containing it in the collection. While indexes like these are incredibly useful to users, we should always evaluate online resources like this. We can start by asking:

- How easy or challenging was it to find the data and methods on the project website and why does this matter?

- What benefits are created by subject tagging or indexing a collection? How can they aid users?

- How can these indexes make records pertaining to historically marginalized people more discoverable?

- What are some issues that may arise?

For example, while every document is drafted and goes through two stages of review by different CWRGM researchers (per CWRGM’s tagging protocols), subject tags are applied by humans and can be overlooked and misapplied in the collection. Furthermore, the boundaries of every subject tag are debatable. For example, how do you apply the African Americans tag when the subject is biracial? The authors’ meaning or intent can also be unclear. Sometimes tags can be added that don’t belong there or should have been added when they do apply. Multiple stages of review and transparency, including providing open access to the project’s protocols or explanatory subject tag annotations, are therefore essential to addressing these concerns.

WHAT IS A CWRGM COOCCURRENCES FILE?

Subject tagging creates an index of the documents within the collection that contain that subject tag. For example, this is an index of all of the documents in the collection that refer to African Americans. A cooccurrences file then exports the other subject tags that were also tagged in documents that received the African Americans subject tag. This file allows users to see what other terms are most frequently discussed alongside that subject tag. Again, users should evaluate these online resources:

- How easy or challenging was it to find the quantitative data and methods on the project website and why does this matter?

- What kinds of information can you find in a concurrences file? How valuable is it?

- Are there potential biases or stereotypes that could be reinforced by the data?

CWRGM users will find, for example, that to obtain other cooccurrences files they must email the CWRGM research team. Balancing a need to protect finalized versions of documents with the technology available to the project led to this decision. But emailing the CWRGM editorial team for cooccurrence data still creates a barrier to access.

COOCURRENCES & REPRESENTATION

Users may also note the potential issues and opportunities regarding representation in the collection’s data. For example, the African Americans subject tag shows a high correlation with tags connected to criminality. This could highlight and even reinforce long standing stereotyping of Blackness with deviance and criminality. Conversely, it also shows that criminal records and criminal proceedings may be a fruitful avenue for exploring Black experiences during the era. This may lead users to investigate white Americans’ use of the legal system to control, restrict, and subjugate African Americans during Reconstruction. It also can reveal Black efforts to resist the racially based adjudication of the law.

People can also be reduced to a group identity in the collection’s data. Where white men, are often readily identifiable by first name and surname, other historically disempowered people are less likely to be found this way. Many women for example are listed as Mrs. David Johnson. Enslaved people are rarely named and when they are, it is typically unclear what their self-identified names were. This document offers a rare opportunity where enslaved people included their first name and surnames. Other groups, such as the patients at the Mississippi State Mental Health Hospital are overwhelmingly referred to as inmates.

Annotations tied to subject tags, however, provide readers with missing information. They also do not alter the transcription of the original text. While CWRGM preferences tagging full names wherever possible, they also add the “African Americans–Enslaved People” subject tag to the document to link all references to enslaved people under one subject tag. This practice allows users to more easily study the experiences of those belonging to a collective identity.

WHAT IS A CWRGM ANNOTATED DOCUMENT?

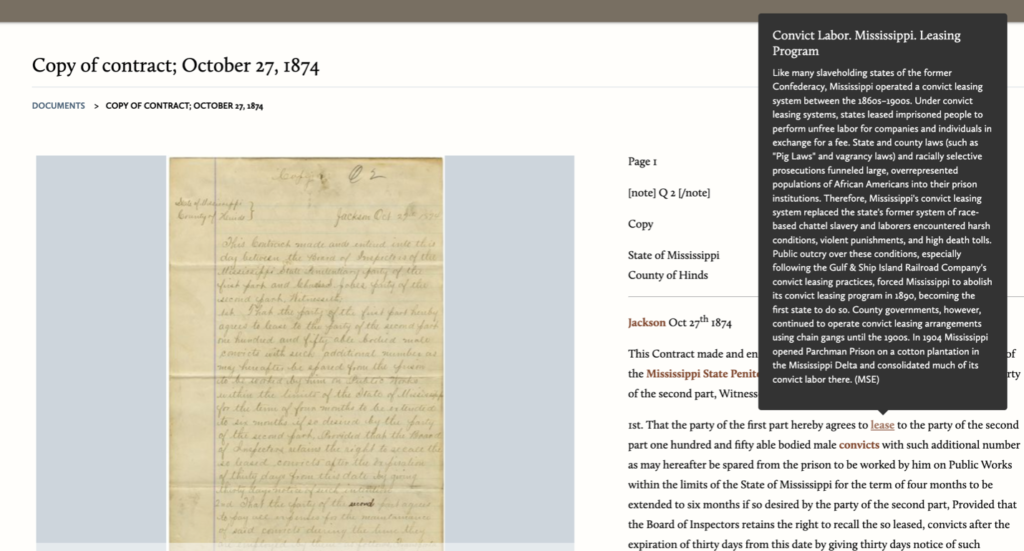

Pop-up annotation for the “Convict Labor. Mississippi. Leasing Program” subject tag on Copy of contract; October 27, 1874. Courtesy of the Civil War & Reconstruction Governors of Mississippi. Click on image to view entire document and transcription.

Pages include an archival-quality digital file of the original document alongside a transcription that includes annotated subject tags. You can see an example here. Subject tag annotations provide users with historical context, explanation, and clarification for how the term is used in the collection. While the document transcriptions and their subject tags produce the collections’ data, the annotated documents themselves offer opportunities to overcome some of the shortcomings of the collection’s data. These possibilities present exciting questions:

- How can reading the qualitative data (documents and annotations) and using qualitative thinking impact what we know, or think we know, about the quantitative data (or subject tagging and cooccurrences files)?

- How does this shape what we know about history/society and our research subject/s?

Data can help point users in fruitful directions, but it contains bias and can be used in harmful ways. Incorporating qualitative reasoning using the documents themselves into our research allows users to discover more about the people within the collection—such as their names, feelings, and experiences—and uncover the human experience where quantitative data often falls short. But there are also limits to what qualitative information can provide. Even with external research, for example, many groups of people cannot be identified by name.

ANNOTATIONS & DISCOVERABILITY

Annotated subject tags and transcriptions offer exciting possibilities for increased access and discoverability in digital editions. Transcriptions, for example, can aid users with disabilities because they can be used in conjunction with online accessibility plugins, where the document images cannot.

Furthermore, adding subject tags within the document offers users (especially students) more appropriate, contemporary naming practices. It is important to keep in mind that not all members of that identity agree on the appropriate terminology or who belongs under the umbrella term.

“Jackson, Mississippi,” Elisaeus von Seutter Collection. Ca. 1800s. Sysid 96984. Courtesy of the Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

Adding annotations to the subject tags can help users learn more about the people who appear in these collections. For example, we can see women’s maiden names or identify the names of an enslaved person without automatically bestowing the enslaver’s surname onto them. Furthermore, historians can offer context in places where the document’s author used coded, inappropriate, or misleading language. For example, when an author refers to penitentiary work, an annotation can provide the greater context about Mississippi’s convict leasing program to highlight the racial inequalities institutionalized within the system.

WHY THIS MATTERS?

Digital editions offer users access to primary sources and historical data on an unprecedented scale but comprise only an infinitesimal portion of the online resources available today. Society has struggled to critically evaluate the mass proliferation of information that has become available with a few quick clicks. The skills to critically evaluate online resources—how they were generated, presented, and maintained—therefore, are paramount. Turning to resources like this lesson plan, the Data Equity Framework, and digital humanities projects like CWRGM can begin to provide users with the tools and resources they need to ask critical questions of online information and most importantly, recenter the human element within the data.

Lindsey R. Peterson, Ph.D. is co-director of the Civil War & Reconstruction Governors of Mississippi Project and the Digital Humanities Librarian at the University of South Dakota (Vermillion). Thanks to funding from the National Historical Publications & Records Commission, she attended the 2023 Digital Humanities Summer Institute (DHSI) where she completed the Critical Pedagogy and Digital Praxis in the Humanities course. An earlier version of this piece was published as “How to Evaluate Online Resources using a Digital Edition,” a blog post she authored as part of her time at DHSI, which can be accessed here.