By Mariah Cosens and Lindsey R. Peterson

The Civil War & Reconstruction Governors of Mississippi (CWRGM) project’s metadata, transcription, subject tagging, and annotation work is accomplished by an incredible team of students from around the nation. Funded by the NHPRC and NEH, CWRGM presently employs seven graduate students, ten undergraduate students, and a high school senior from Mississippi, South Dakota, Illinois, and New York. Their time with the project provides students with hands-on training and experience in documentary editing, historical research, and DublinCore metadata, and many of our past student researchers have gone onto to rewarding careers in libraries, archives, and museums or to continue their graduate-level education in these fields. Their dedication, skill, and commitment are essential to our ability to make these critical historical records freely available online at cwrgm.org, and we believe their training and professional development is crucial to creating a truly collaborative, community-minded digital documentary edition.

This winter, CWRGM co-director Dr. Lindsey R. Peterson sat down with Mariah Cosens, a member of the CWRGM annotation research team and a first-year master’s student in the history department at the University of South Dakota, to discuss her work with the project. In the subsequent interview, Cosens highlights many of the important skills CWRGM student research assistants develop during their tenure with the project and the importance of this work.

Peterson: Hi Mariah. Thank you so much for agreeing to chat with me. Please tell us about yourself.

Cosens: My pleasure. I’m Mariah Cosens, a first-year master’s student in the history department at USD, and I did my undergraduate degree in history at the University of Sioux Falls before coming here. I’m interested in twentieth century African American history and my thesis focuses on a Black-owned restaurant in southwest Missouri and how, amidst segregation, it created a safe, communal leisure space for Black soldiers deploying out of Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri during World War II. I am also pursuing a certificate in archival and museum studies at the university and am a researcher on the annotation team for CWRGM. I am also a mother of two young daughters and am married.

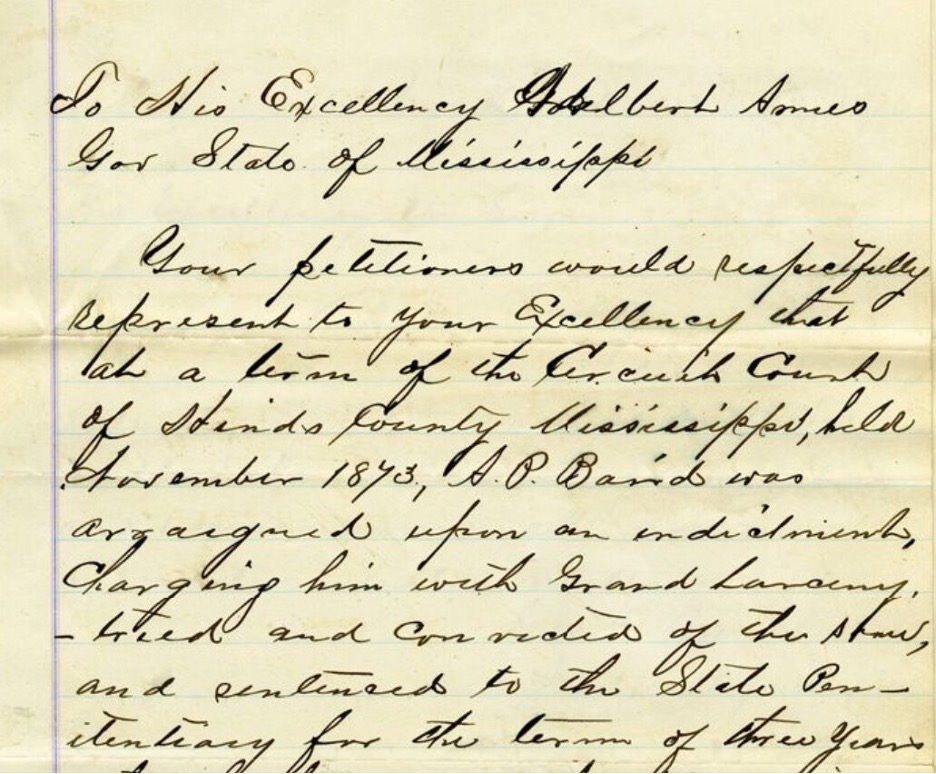

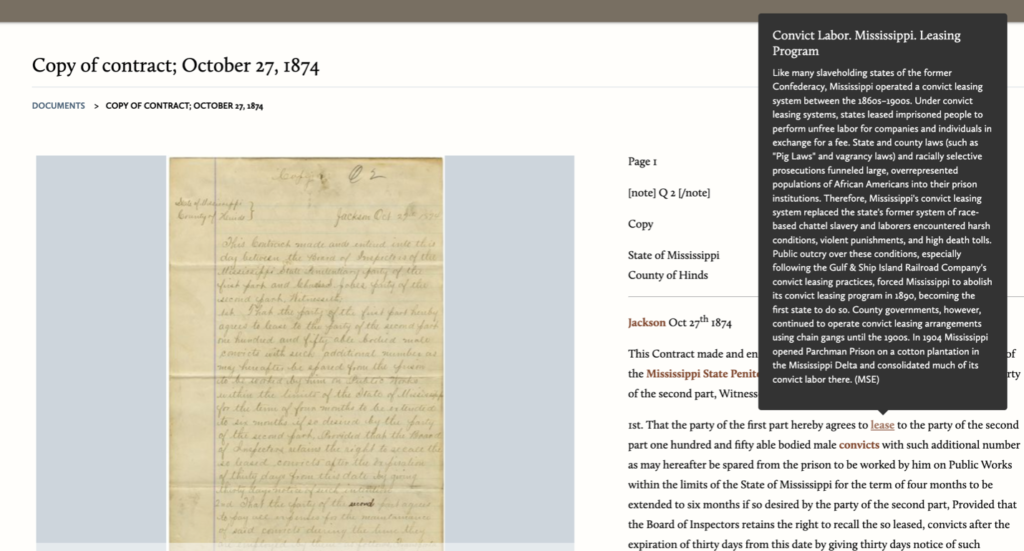

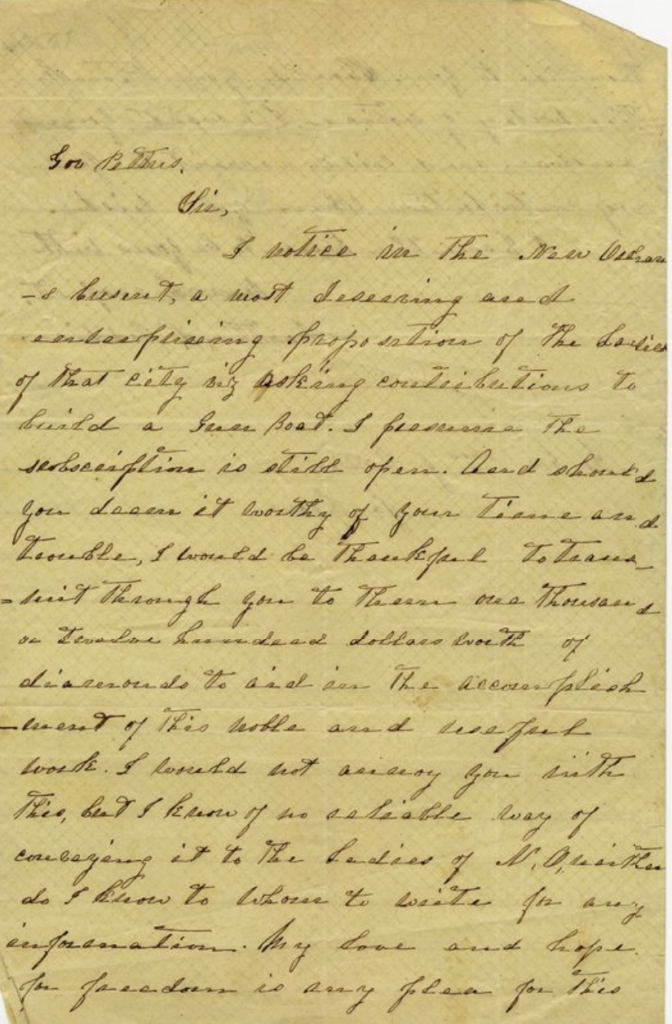

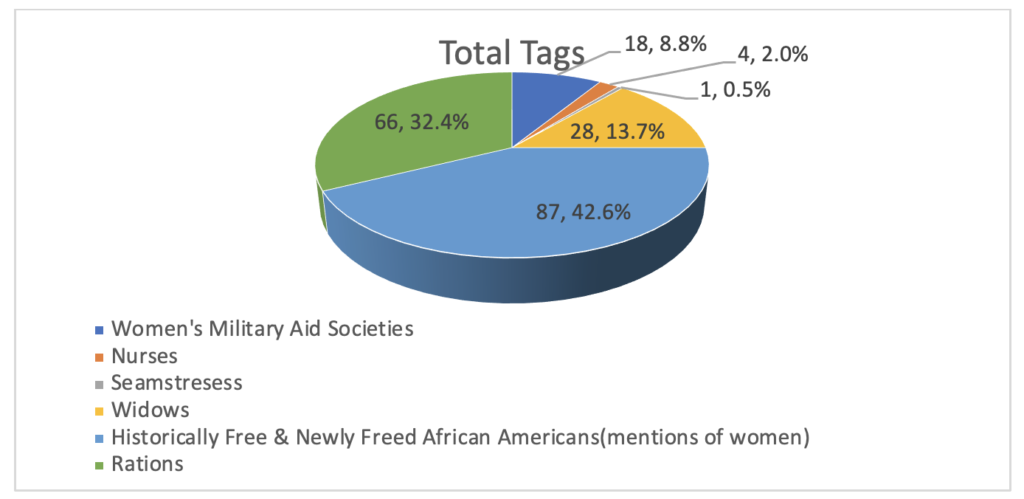

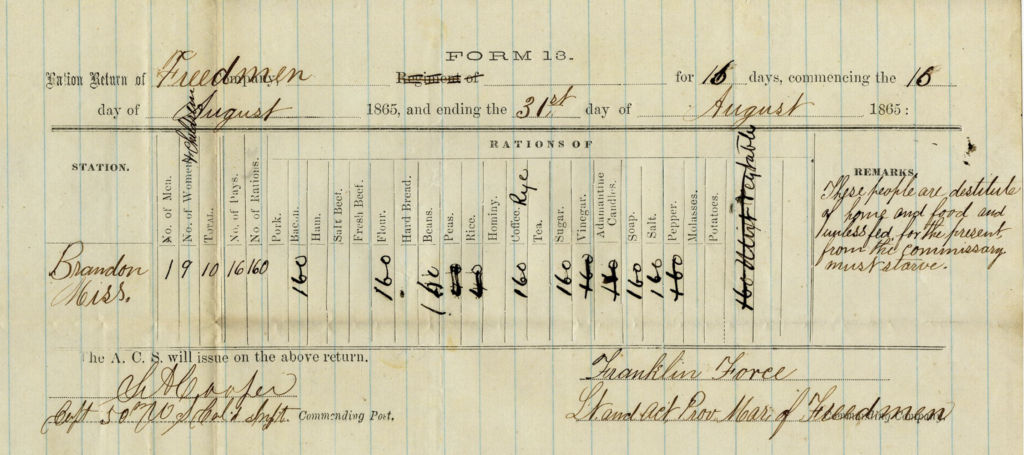

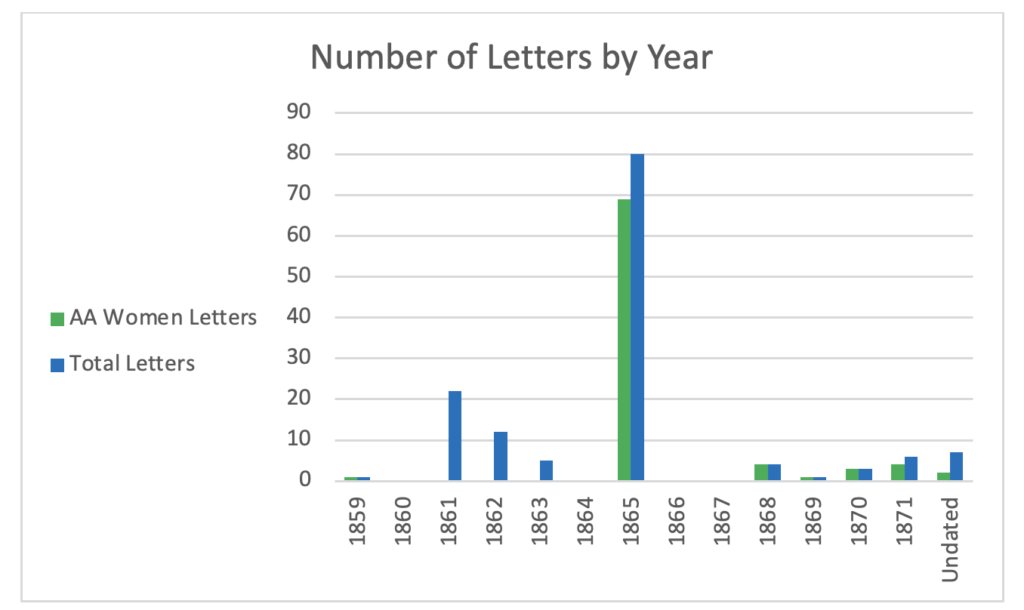

Peterson: Thank you; you’re a very busy person. I suppose I should explain a bit about CWRGM’s background for readers. CWRGM, or the Civil War & Reconstruction Governors of Mississippi project, is a federally funded digital documentary edition. With the financial support of the National Endowment of the Humanities and the National Historical Publications and Records Commission, we are digitizing over 20,000 documents that were sent to the governors of Mississippi from 1859–1882. Many people incorrectly assumed that these records are from the governors themselves, but they are actually from an incredibly diverse body of authors. You can hear from women, impoverished people, soldiers, veterans, and even freed African Americans, among many more constituencies. Essentially it was like the Twitter of the era; just about everyone wrote to their governor. Once we have archival quality scans, student researchers write metadata for the collection, transcribe the original documents, and identify key terms in the collection. These key terms then become hyperlinked subject tags, allowing users to find any document in the collection that also shares that term. This is where the annotation team comes in. So, please tell us about your role with CWRGM.

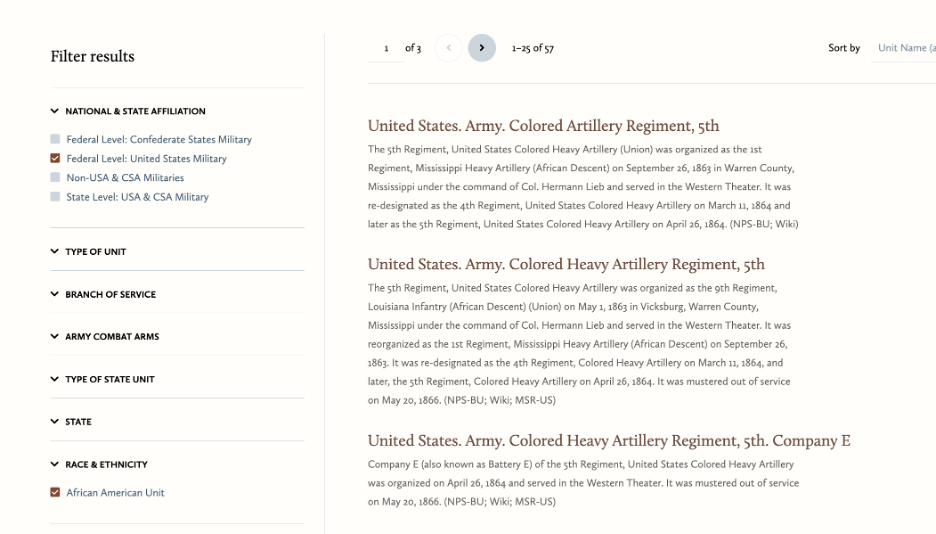

Cosens: Well, I’m currently a research assistant for the annotation team. I was approached by you about a job openings for graduate students on the project, and I wanted to apply because it would connect my background and interest in Black history with digital and public history and expand my skills. My job on the project is to research those key topics that appear in the collection and give context to users to help them better understand this pivotal period. For example, when references to topics such as mass racial violence, like the Yazoo Race Massacre, appear in the collection, I draft up narrative and contextual explanations of what these events were. Essentially, I help users better understand what they are reading and about the complexities of this era, like the relationship between white and Black Americans during Reconstruction.

Peterson: Well said. Tell us about a favorite key term that you have worked on.

Cosens: That would have to be my annotation for the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act. It was fun to research and not just explain what the act itself was legally, but I also got to contextualize what previous laws had done and what its larger impact was, especially for those enslaved people who emancipated themselves. Relating the complexities of how people experienced the act was challenging, interesting, and important to work on. Annotations like this one really help me to become a better writer because I have to take a lot of complicated history about a topic and boil it down to a brief annotation that anyone from a grade school student to a scholar to a genealogist can understand.

Peterson: That is a great example. What topics are you looking forward to working on?

Cosens: Probably the annotations on the people that show up in the collection. I think that will be really interesting because I am excited to start seeing people overlapping in specific causes and become familiar with them. Sometimes historians feel as though they are acquainted with the people in their research, and I am eager to learn more about their life paths, their struggles, the decisions they made and why they communicated with their governors. Plus, this is where we will really start to identify Black authors by name and flesh out the lives of people who so often go unnamed in history. I also just started work on annotating organizations and that has been fascinating as well because these annotations become spaces where I get to tell broader stories about the past. It is so important to see how individuals impacted a historical narrative and it’s always enjoyable expanding my historical knowledge.

Peterson: I agree, the collection is full of interesting people and topics. How has your work with CWRGM connected with your studies in the history department’s master’s program at USD?

Cosens: The work is fascinating and has taught me a lot of valuable research skills, especially the importance of digital research skills and resources. I often research in online historical newspapers, journals, military records, and the census. And working from South Dakota to find quality primary sources on Mississippi’s history would be impossible without digitization. Not only that, but the sources I am helping put online will also become resources for other students, genealogists, and scholars in their own research, and I have even been able to contextualize my own research better. The themes I find from working on past annotations pertaining to CWRGM’s African American history have helped me to draw connections to my own thesis work, so that’s been really cool to see. As a student, it’s refreshing when your employment mirrors the skills required in your educational path. I get paid to hone these skills, and then I can deploy them directly into my own coursework.

Peterson: That is fantastic! So many of the skills needed to create these editions are applicable to future careers for humanities students. That has certainly been my own experience. So, what’s surprised you in your work at CWRGM?

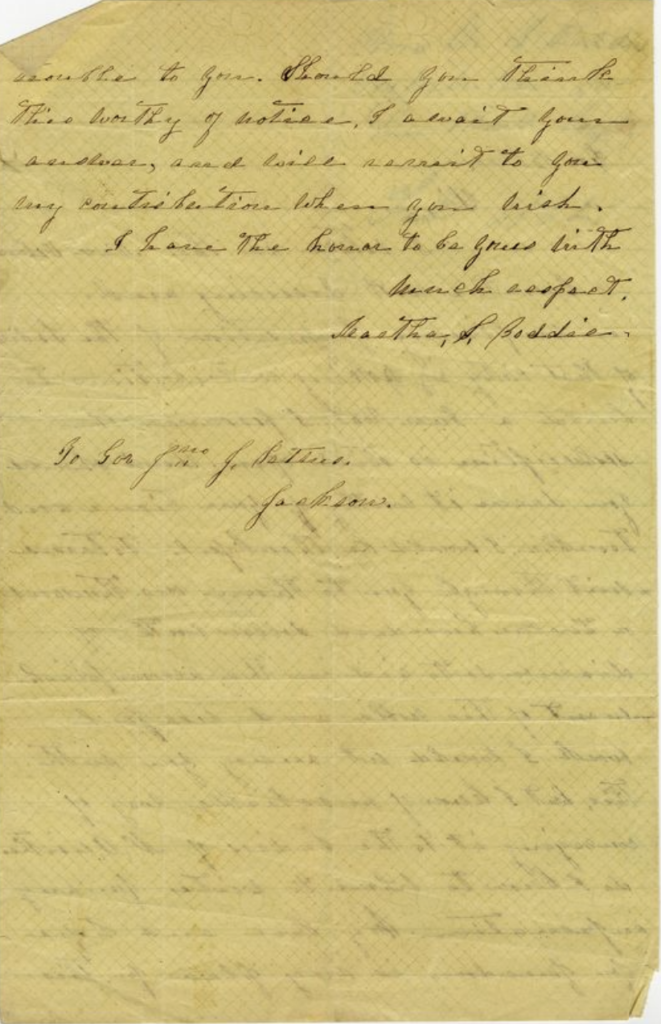

Cosens: I forgot how hard it is to read cursive. (laughs) What is annoyingly surprising is how in the nineteenth century there were not given names to places, so there are all of these locations that existed then and were known colloquially, but they don’t exist anymore. Or at least they no longer are recognizable by their former names, so those terms have been difficult to locate. An example would be Harrison Station, Mississippi. Often these older towns or unincorporated areas were known colloquially through who first purchased and settled the land, but they’ve been subsumed by larger incorporated towns and cease to exist or are just a populated area in a county now. Finding locations like this really takes some digging. I went through many sources with Harrison Station, but none were verifiable or quality sources, so I had to keep researching. Eventually I found a history of the county that finally gave a substantial history to Harrison Station, its settlement dates, and other general context that would have been lost to the ages without the digitization of the source I used. Some days this job feels like a treasure hunt! But I find it very rewarding to finally locate a difficult to find location, person, or organization.

Peterson: You’re essentially a historical detective! What are some of the challenges of the job?

Cosens: The size of the tasks in front of me can be a challenge. Some of these terms are huge, so where do I start? How do I boil down an experience like emancipation, with all of its diversity and impact, into a few sentences or paragraphs? It is a monumental task. The reverse is also true. I would also say that learning to be okay with not being able to identify a term and accepting that can be very difficult. Sometimes you can find information about a key term but cannot verify it with quality sources, so you have to move on. Other times you can’t find anything about that topic. It is just lost to history.

Peterson: That is very true. Before we wrap up, please tell us about your future work with CWRGM and your own career goals.

Cosens: Well, I still have a year and a half left in my Master’s, so I’ll be finishing my coursework and my thesis. I’ll also continue with the annotation team but am interested in learning more about digital editing, and CWRGM is a place where I can gain those skills. Concerning the long term, though, I am leaning towards going into some type of public history field but am open to anything where I can use my historical research and writing skills. I am especially interested in digital research and connecting history to the public in digital spaces, so my training with CWRGM is invaluable to learning digital workflows, research, and communication. My interests have primarily been in African American history, but I’m also open to working on public history concerning United States history at large, too. If I could keep doing something as flexible, accessible, and fascinating as this work long-term, I would be delighted!