By A. J. Blaylock

In the Spring of 1863, General Ulysses S. Grant began his campaign to capture the city of Vicksburg, Mississippi. As Grant pursued his indirect course to the city and eventually laid siege to it, Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton, Governor of Mississippi John J. Pettus, and Confederate President Jefferson Davis frantically telegrammed each other about how to proceed. Their messages underscore the Confederate high command’s waning confidence in each other and their ability to protect the Gibraltar of the Confederacy.

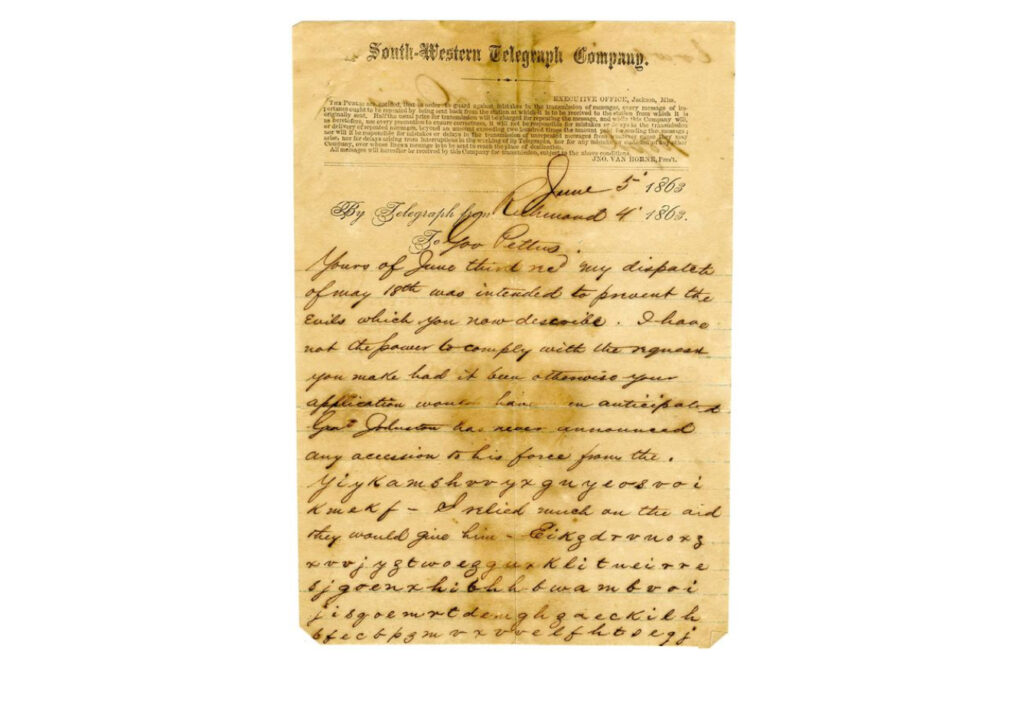

Pemberton, in a telegram to Pettus on May 1, 1863, indicated that despite Confederate resistance, “there will be ten thousand troops at Jackson in a few days.”[1] A month later, with the city of Vicksburg well under siege, President Davis reminded Governor Pettus of the lengths to which the Confederacy had already gone to reinforce the Vicksburg and declined interest in doing any more. On June 5, Davis informed the governor that he “had not the power to comply with the request” Pettus had made for more troops. He then called into question whether Mississippi was adequately using the forces it already possessed. Davis pointed to the fact that there had been no efforts to draw from “the militia or exempts of the state” and concluded that “to furnish the reinforcements sent to Mississippi” already, the Confederacy had “drawn from other points more heavily than was considered altogether safe.”[2]

This correspondence between Davis and Pettus only soured. As Vicksburg languished under siege, Davis again telegrammed Pettus that the “withdrawal of thirty thousand troops as suggested” by Pettus, from another part of the Confederacy to reinforce Vicksburg, would ultimately have to come from Middle Tennessee where they could not be spared. Davis acknowledged the importance of the situation at Vicksburg but nonetheless expressed discouragement that the governor’s recent communications indicated “no reliance on efforts to be made with the forces on the spot.”[3] Davis thereby indicated a declining faith that either Pemberton or Pettus could sustain Vicksburg with any number of troops.

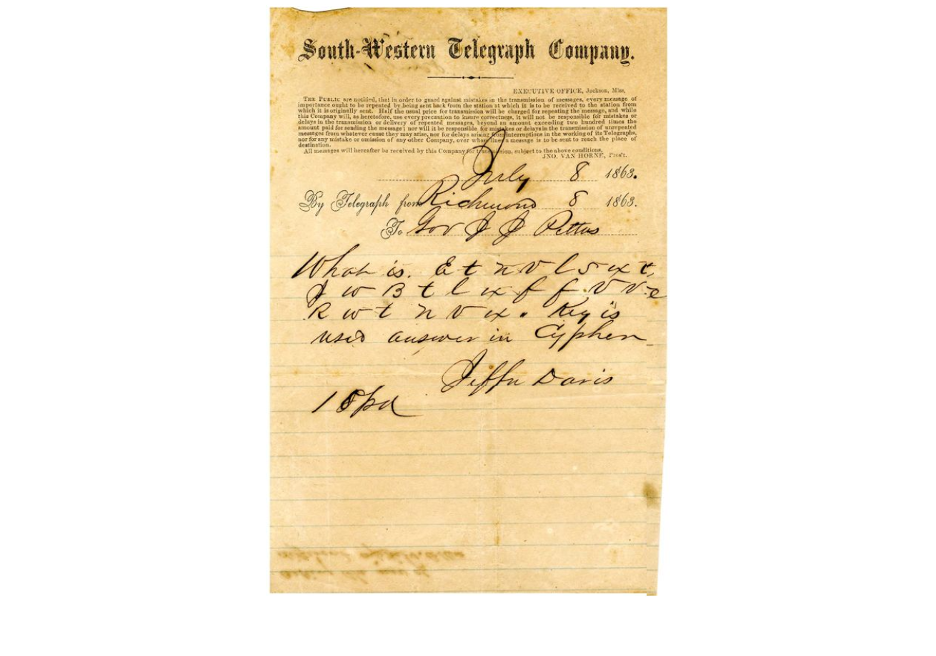

By July 8, four days after the city belonged once more to the United States, a despondent Davis could only ask Pettus “what is the state of affairs at Vicksburg?”[4] The next day, Pettus informed the Confederate president of Vicksburg’s surrender but remained hopeful. He wrote Davis that Vicksburg had indeed fallen on their former nation’s anniversary “for want of provisions,” rather than unwillingness to fight. However, he maintained that “twenty-two thousand officers retain side arms and private property…and remain prisoners of war until exchanged. If arms are promptly sent them and the exchange pressed to a speedy completion Miss. may yet be saved.” Less optimistically, Pettus noted that the Federals were then within seven miles of Jackson and “battle expected.”[5]

These communications between Davis, Pemberton, and Pettus underscore growing divisiveness within the Confederate high command. Such telegrams threatened to boost Union morale and, in Pettus’ case, foil their military strategy, if leaked to the national public. To stave off such an eventuality, each of the above communications was written in code.

Telegram from Confederate President Jefferson Davis to Mississippi Governor John J. Pettus; June 5, 1863. Courtesy of the Civil War & Reconstruction Governors of Mississippi. Click on image to view entire document and transcription.

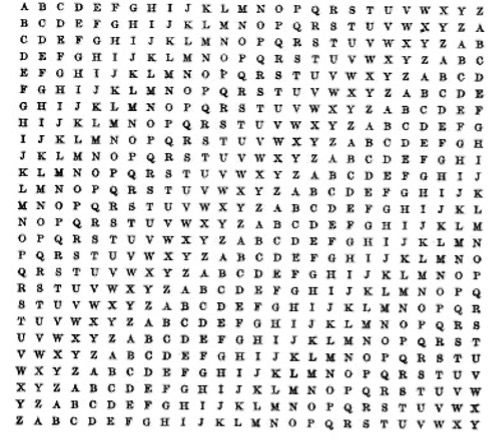

Davis, Pemberton, and Pettus all adopted a substitution cipher known as a Vigenere cipher to encrypt their messages. It’s popularity among the Confederacy’s leaders, particularly at Vicksburg, produced its contemporary nickname, the “Vicksburg cipher.” As a substitution cipher, each letter in the original document is “substituted” for a coded letter based on a specific encryption pattern. The root of that pattern is a word or phrase that serves as the key to writing and then deciphering the code. The Confederacy used multiple keys including the most popular “Manchester Bluff.” If one has the key and the encoded letters, then deciphering the message is relatively straightforward. Vigenere ciphers work off an alphabetical grid like the one below.

This grid is a copy of one presented to the Union Assistant Secretary of the Navy in 1865. Reproduced in “Overview of Civil War Codes and Ciphers” courtesy of Cryptiana.

The keyword indicates the correct horizontal row. So, if the first letter of the key phrase is “m” as in “Manchester Bluff,” one should start on the horizontal row that begins with “m.” If the first letter in the coded message was then “I” as it is in the June 21 telegram from Jefferson Davis, the decoder would move horizontally along the row beginning with “m” until reaching the letter “I.” The letter at the top of that column indicates the author’s meaning, here the letter “w.” Locating each letter, then, becomes a matter of navigating the grid in a backwards “L” shape.

Writing the code would require working backwards, locating the true letter at the top of the grid and going downward along that column until reaching the horizontal row indicated by the keyword. The axis of the two would produce the coded letter one would write down. CWRGM’s documents only contain coded letters, but fortunately other historians have located the common keyword “Manchester Bluff,” which I adopted as a starting point when working on the documents as a graduate research assistant.[6] I wrote each letter out longhand to make it easier to see how the letters lined up, placing the keyword at the top, the code underneath, and the prospective meaning at the bottom. For example, to get the meaning of Davis’s June 21 telegram, I wrote:

| Key | M | A | N | C | H | E | S | T | E | R |

| Code | I | L | G | J | K | V | S | P | E | C |

| Meaning | W | I | T | H | D | R | A | W | A | L |

Fortunately, Davis, Pettus, and Pemberton were kind enough to universally use “Manchester Bluff” as their key, saving Union Army codebreakers and impatient graduate researchers much trouble. Perhaps due to the haste required by their circumstances, Pemberton and Pettus even preserved the correct spacing between each word, whereas in the rest of the documents I had to parse out the words for myself from a lengthy, unbroken chain of letters.

Aside from offering an interesting puzzle to sort out, these codes underscore the CWRGM database’s usefulness to researchers. The documents mentioned above embody the urgency and anxiety felt in a Confederacy faced with the loss of one of its most important cities, and their staunch hope of preserving the Confederate war effort despite it. They also provide a window into the decision-making and internal bickering of an army on its heels. Not only did Davis, Pettus, and Pemberton sharply disagree over how to proceed, and make subtle jabs at each other’s efforts, they took infinite pains to keep those disagreements secret from Union interceptors and, if unintentionally, historians. While the decoding of ciphers from Vicksburg is not new, CWRGM’s effort to provide deciphered transcriptions of these documents is ensuring that even documents designed specifically for secrecy are available and accessible to wide audience. CWRGM’s database thereby highlights the digital humanities’ role in pushing historical inquiry further by exploring not only the content of historical documents but the often more insightful forms of that content.

In this July 8, 1863 telegram, Confederate President Jefferson Davis writes in a Vigenere Cypher and requests that the governor respond likewise. Telegram from President Jefferson Davis to Mississippi Governor John J. Pettus; July 8, 1863. Courtesy of the Civil War & Reconstruction Governors of Mississippi. Click on image to view entire document and transcription.

A. J. Blaylock is a Ph. D. student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He holds a B.A. in History from the University of Southern Mississippi and an M.A. in History from the University of Alabama. He has worked on three different Civil War Governors projects in Mississippi, Alabama, and Kentucky and is currently an Assistant Editor for the Civil War and Reconstruction Governors of Mississippi Digital Project. His current research focuses on the intersections of race, military service, and historical memory in the nineteenth-century U. S. South.

[1] “Telegram from General John C. Pemberton to Mississippi Governor John J. Pettus,” May 9, 1863. Civil War and Reconstruction Governors of Mississippi, https://cwrgm.org/item/mdah_762-948-08-37.

[2] “Telegram from Confederate President Jefferson Davis to Mississippi Governor John J. Pettus,” June 5, 1863. Civil War and Reconstruction Governors of Mississippi. https://cwrgm.org/item/mdah_762-948-09-06.

[3] “Copies of Telegram from President Jefferson Davis to Mississippi Governor John J. Pettus, June 1863. Civil War and Reconstruction Governors of Mississippi. https://cwrgm.org/item/mdah_762-948-09-24.

[4] “Telegram from Confederate President Jefferson Davis to Mississippi Governor John J. Pettus, July 8, 1863.Civil War and Reconstruction Governors of Mississippi. https://cwrgm.org/item/mdah_762-948-10-09.

[5] “Letter from Mississippi Governor John J. Pettus to President Jefferson Davis; July 9, 1863,” Civil War and Reconstruction Governors of Mississippi. https://cwrgm.org/item/mdah_757-945-04-25.

[6] “Overview of Civil War Codes and Ciphers.” Cryptiana. http://cryptiana.web.fc2.com/code/civilwar0.htm.; Jones, Terry L. “The Codes of War,” New York Times, March 13, 2014. https://archive.nytimes.com/opinionator.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/03/14/the-codes-of-war/.