by Meghan Sturges

The Civil War and Reconstruction Governors of Mississippi Project (CWRGM) provides amazing opportunities for its graduate assistants. I was lucky enough to serve as a metadata graduate assistant for the past two semesters while finishing a degree in Library Information Science. When choosing a topic for my thesis, I knew I wanted to analyze CWRGM to highlight how one can use this archive to find accounts of marginalized communities, like women. Using quantitative analysis, I focused on letters written by women and about African American women. Both are under-represented in narratives about the United States Civil War era, and I wanted to see if metadata and subject tagging made correspondence in both categories easier to discover.

Before digging into the analysis, one must understand how CWRGM uses the metadata and subject tags to enhance this archive. CWRGM uses a version of metadata tags established by the Library of Congress (LOC) subject authorities and subject tags created by CWRGM project leads using controlled vocabulary. Developed to fill in gaps that the metadata tags do not quite satisfy, these subject tags are what allow traditionally minimalized/marginalized groups to become more discoverable in the CWRGM archive. For example, the subject tag Historically Free and Newly Freed African Americans was used in my research. This subject tag covers a variety of groups and experiences that researchers may not think to use when searching or terms that are now considered offensive and/or outdated. What CWRGM has done is make content more accessible by being thoughtful with its use of language.

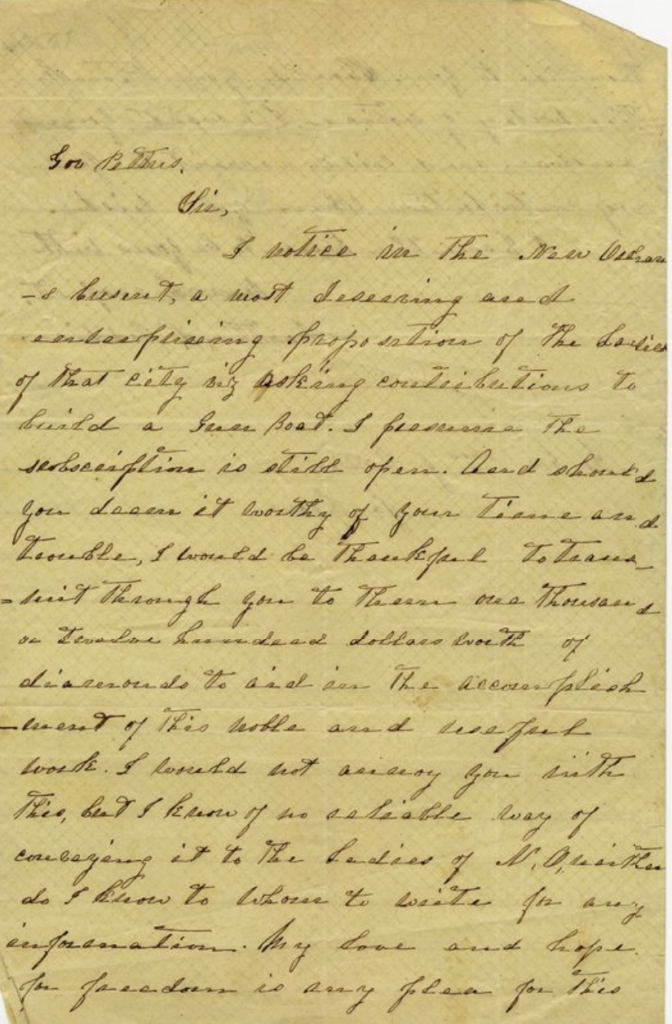

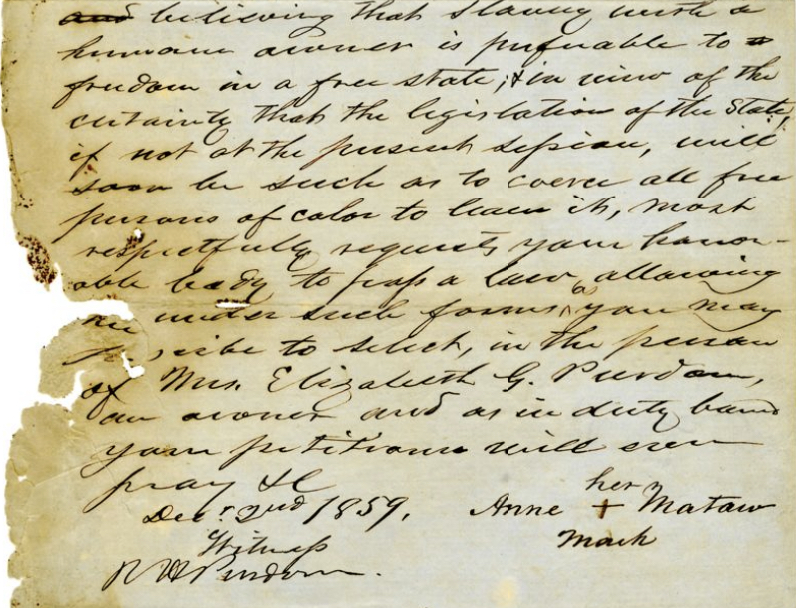

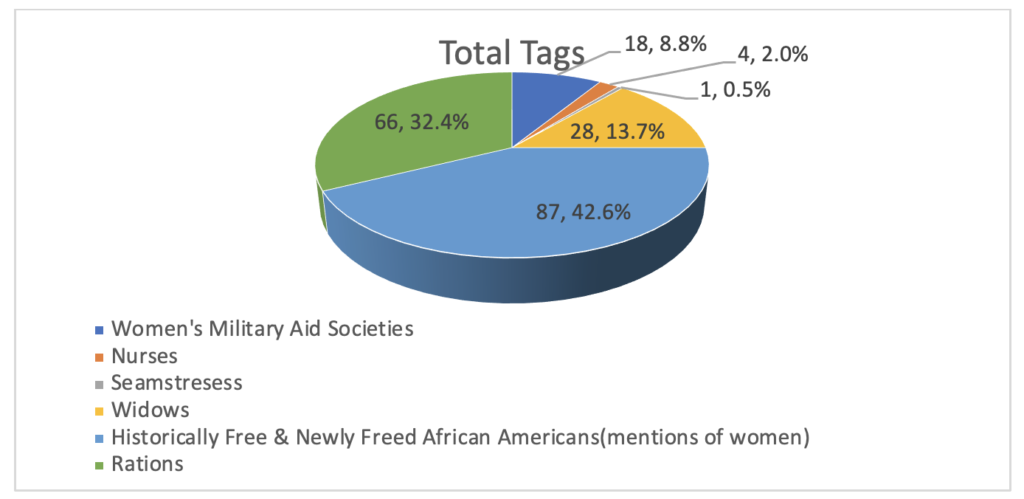

As I began my analysis of the site in the Fall 2022, first I browsed the Explore the Collection page for any subject tag that revealed groups of women.[i] After examining the list of categories, I chose several for further investigation: Ladies Military Aid Societies, Widows, Nurses, and Seamstresses. The results indicated that southern white women were prolific participants in the Civil War. Of the 180 letters examined from this specific search, 57 or 31.6%, were written by women. Ladies Military Aid Societies had the most letters written by women, where 33.9% of all letters under this category were authored by women. These messages demonstrate that women raised funds, sewed uniforms, volunteered as nurses, and one woman, Martha S. Boddie, even offered her jewels to buy a gunboat for the Confederacy (see below).

Letter from Martha S. Boddie to Mississippi Governor John J. Pettus; February 1862. Courtesy The Civil War & Reconstruction Governors of Mississippi. Click on image to view entire document and transcription.

The second largest category of women writing letters is under the section for Widows. Of the 103 letters that appeared under the term Widows, 34 were written by women. As one can imagine, the war created many widows and many of these letters are from women made desperate by the loss of their source of personal and financial security. Multiple widows, for example, asked to have taxes waived or requested they be pardoned from crimes committed to support their families. In one situation, Martha Craigan wrote to Governor Charles Clark in 1863, complaining of her cotton being burned as she and her neighbors were traveling to exchange the cotton for other goods. Craigan laments, “I never would have attempted it if necessity had not had drove me to it, having been deprived of the necessaries of life for the last three years, with a large and helpless family of girls, with no husband or son to assist in making them a support.” Despite appealing to local military officials, they could offer no assistance and referred her to the governor. Many women like Craigan were left in dire situations, and Confederate state legislatures worked to find ways to increase support for military families throughout the war.[ii]

Table A: Percentage of Letters Written by Women

by Metadata and/or Subject Tag

The documents relating to African American women’s experiences were even more exciting because for too long they have been silenced in United States history. Some of this is, scholars argue, is due to the limited sources available. It was illegal for African Americans (freed or enslaved) to learn how to read or write in much of the Antebellum South, and Mississippi was no exception.[iii] So, it is fair to say less African American-authored material is available for archivists and historians, but it is not impossible to hear their voices, as scholars have increasingly shown over the last several decades. In part, this is done by looking through the narratives of others to find information. The CWRGM subject tag Historically Free and Newly Freed African Americans helps with this, and I explored these for this search. At the time of the investigation, I located 238 documents of which 83 or 34.8% mentioned African American women. To be clear, many of these documents are written by white people and, as a result, carry a white interpretation of a Black person’s experience. Still, some documents are by African-American authors and used alongside other accounts by whites, they can offer examples of African-American women’s experiences before, during, and after the Civil War.

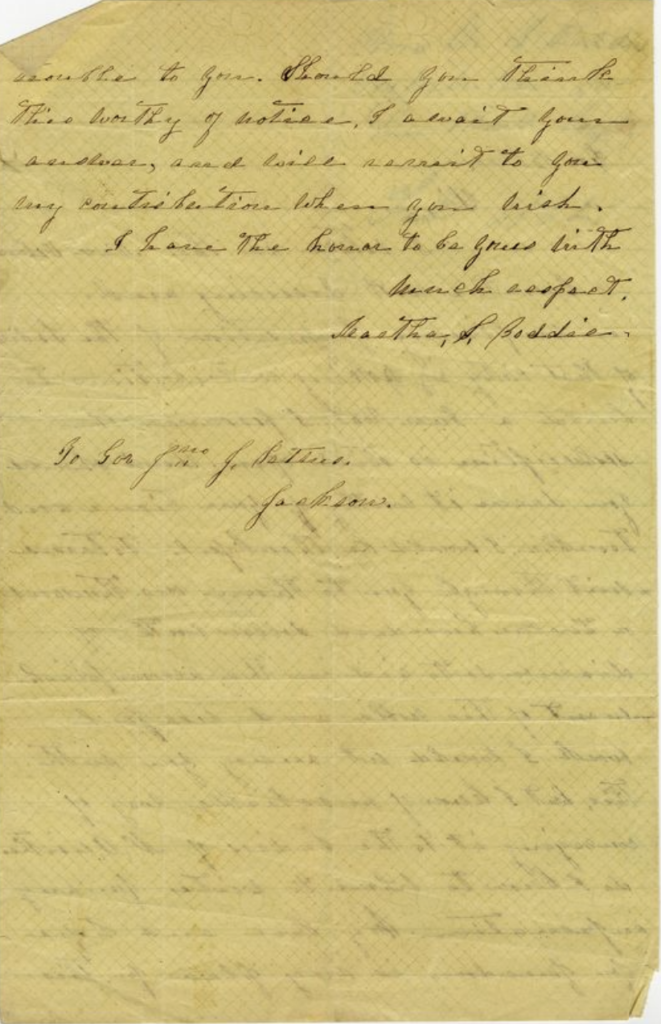

The largest number of letters about African American women were written in 1865, right at the war’s end. Many of these take the form of issued rations and food given to Mississippians from all walks of life by the Union Army. The documented rations in Table A represent only those issued to African American women, 66% of the letters examined in this analysis. Beyond being identified as female and African American, most of these ration cards give little information about their recipients. Still, data can uncover powerful stories, and the data relating to rations tells a tale of need. A possible way for this to be further studied is to examine any correspondence or journals written by the Union officers issuing the ration cards. A few specific officers issued many ration cards, and personal reflections may provide more details about African American women and others who needed rations. Another approach is through census, newspaper, and pension records, which may offer more information about the women’s experiences. Below is a Ration return of Lieutenant Franklin Force, in which 15 days’ worth of rations were issued to one male and nine female freedmen in August of 1865.

Ration return of Lieutenant Franklin Force; August 16, 1865. Courtesy The Civil War & Reconstruction Governors of Mississippi. Click on image to view entire document and transcription.

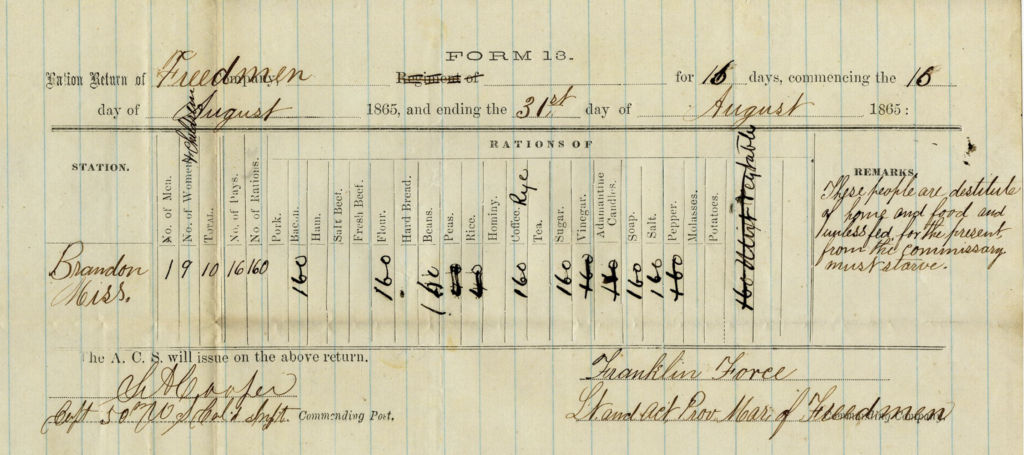

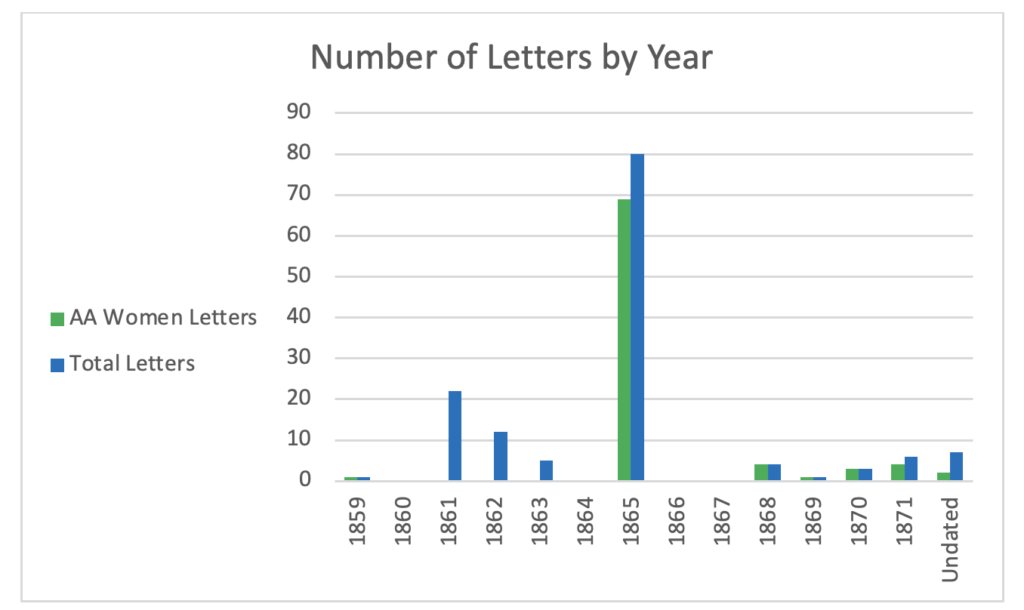

As shown in Table B below, much of the correspondence—of the documents currently available online—referencing African American women did not appear until after the war ended. Only one document was written before the war, in 1859. Twelve were written after the war; four in 1868, one in 1869, three in 1870, and four in 1871. These are not happy letters. They tell stories of murder, exploitation, and cruelty against newly freed African American women. The first letter to appear in the search referring to an African American woman was from Sheriff Robert Meeks describing the murder of Lucy McCormick, a young African American girl shot to death.

Table B: Number of Letters by Year

One does not have to be a historian to find value in these archives. CWRGM offers excellent opportunities to study metadata, highlighting the role that archival methods play in making collections more discoverable for researchers. For me, that was the most significant impact of this project, which explored the efficacy of the CWRGM metadata and subject tags. The goal was to find narratives of women, and using the website’s guidance, that was simple to do.

[i] Data for this project was based on research conducted in the Fall of 2022 and the Spring of 2023; the documents and subject tags available at cwrgm.org are always growing and evolving, so this data may not reflect what is currently available at the site.

[ii] See, for example, Stephanie McCurry, Confederate Reckoning: Power and Politics in the Civil War South (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010).

[iii] Christopher M. Span, “Learning in Spite of Opposition: African Americans and Their History of Educational Exclusion in Antebellum America.” Counterpoints 131 (2005): 26–53.

Meghan Sturges is a native Mississippian graduating with her Master of Library Information Science in May 2023 from the University of Southern Mississippi. She served as a research graduate assistant for CWRGM for the Fall 2022 and Spring 2023 semesters. She has worked as a history teacher at Pascagoula High School for the past seven years. After graduation, she plans to pursue a career in Academic Librarianship.