by Sarah West

To be unenfranchised does not mean that one is voiceless, nor does it mean that one must sit idly by and let the world move around them. The women of Mississippi had no official political power in the 1800s, but this did not stop southern white women from participating in political acts. They took part in political conventions as early as the 1830s to defend slavery, balked against the interventions being made on their domestic fronts, and engaged with the political process by taking their complaints directly to the executive officer of the state.

We can find examples of those direct interactions in the records of the Civil War & Reconstruction Governors of Mississippi (CWRGM) project, which is digitizing the state’s governors’ papers from 1859 through 1882. These letters make it possible to hear from these women who called upon their governor for various reasons before, during, and after the Civil War. In this three-part series, we will look at how the nature and volume of these letters changed over this period and study these women’s experiences in such revolutionary times.

There is no way to gauge within this collection of letters how often women wrote the governor before the Civil War started. Still, within the span we can access, we can see that the frequency increased drastically as the war went on. Seven letters stand out from the period of April 1860 through April 1861 that reflect this trend, and each reveals women engaging in the political process to protect their family or their family’s interests. The first letter, dated April 29, 1860, comes from Jane White, who asked Mississippi Governor John J. Pettus to pardon her husband’s criminal charges. He was sentenced to five years for stealing an enslaved person. Jane gives a testament to her husband’s character but admits that it’s not “misery, trials or troubles,” but the “tender tie called love” that prompts her request. This letter stands out in the collection because of the motive in which she pleads for her husband’s return. When the war begins, the reasoning for requesting the return of a loved one predominately leaned toward safety and sustaining the family rather than the affection expressed in this instance. Serving in the war was a duty, and now soldiers’ families were expected to sacrifice the absence of their loved ones for the greater good.

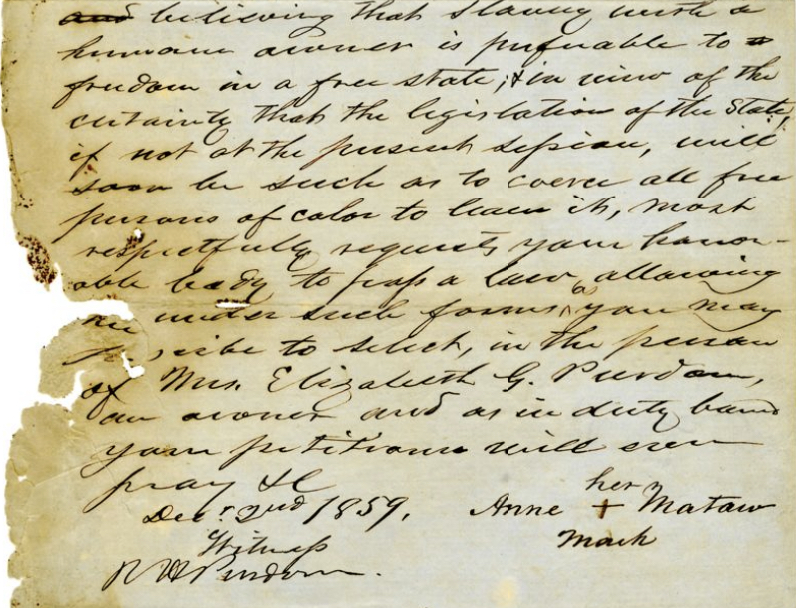

It’s significant, too, that Jane White reveals no thought about how her husband’s actions may have damaged an enslaved family. The voices of African-American women are rare in the pre-emancipation portion of this collection. Still, we can find glimpses of their experiences and how white arguments about protecting the white domestic sphere could affect them. Five months earlier, for example, Governor Pettus received a petition from a free woman of color named Anne Mataw. Mississippi laws at that time made it almost impossible for her to remain in the state and remain free, so Mataw made the gut-wrenching decision to be enslaved or re-enslaved. Her petition includes Mataw’s mark, but I have found nothing else about her (yet). Did Mataw do this to protect her own family as best she could? Was this the only way she could remain near her children or husband? Scholars have argued that these were common motivators in re-enslavement petitions rather than the reason the document suggests that “slavery with a humane owner is preferable to freedom in a free state.”[1] By no means are Mataw’s experiences the same as those of the white women described in this post. But like them, she may have used the governor’s office to protect herself and her family.

As tensions escalated throughout the 1860 election year, petitions from concerned women continued to arrive on Governor Pettus’s desk. In each case, the author made her case on the grounds of domestic security and family preservation. In October 1860, for example, Mary Garrett wrote on behalf of her son, who was being held on charges she never clearly defined. In this letter, Garrett reminds the Governor that she came before him with a petition for her son’s release last February. She also notes the Governor’s failure to follow through on his pledge to speak with a Judge Cothern about her son’s case, stating, “I suppose you forgot me, as the Judge states he—never got your letter he also states he was with you last July and not knowing you had a petition never hearing of your receiving any information relative to the case.” Garrett argues that Cothern assumed Pettus would have dismissed the charges and then softens her approach by asking Pettus to acknowledge that wisdom comes with age and that her son has grown up since his infraction. She asks Pettus to empathize with her, encouraging him to recall his own affectionate mother and what she likely did for her children. Determined to save her son, Mary Garrett wrote another letter that day to Major Alfred Harden that conveyed her situation and requested him to write to Pettus on her son’s behalf. It is within the scope of these interactions that we see Mary Garrett was comfortable enough to petition the Governor in person, to follow up with the Judge that is mentioned, to hold Governor Pettus accountable to his commitment, and to encourage another man of standing to intervene as well. As scholars have noted, though 19th-century women were disenfranchised, they still found ways to navigate the political realm and often did so with arguments about their familial duties as dedicated wives, mothers, or daughters.

We can see another example of this in a November 1860 letter from Mrs. J. M. Girault asking to be released from the debt that her husband incurred. She explains that if she were to repay the debt, it would leave her and her children homeless or drain her father’s estate. It is unclear whether or not Mrs. Girault owned property, but she does state that she is not requesting to be released from her half of the debt and claims that if it had been in her power to do so, the debt would have never been incurred. Mississippi was the first state to allow married women to own property; this law was enacted in 1839 and meant that a married woman’s property could not be seized to pay her husband’s debts.[2] This letter suggests that Girault still retained the means to pay her half of the deficit and her willingness to assert herself to protect her family’s financial standing.

Though the Civil War started on April 12, 1861, Mississippi seceded from the Union four months before this date, meaning militia were already forming in the state. When the Copiah Horse Guard mustered into service in March 1861, Josephine Martin tried to ensure her husband did not join the unit. She asked Governor Pettus to exempt her husband from service because her “health was bad and [she] needed his attention at all times.” She admitted that “his business also (not being settled up)” required attention, but it’s worth noting that the first concern Mrs. Martin asserted focused on her immediate needs. Indeed, the document is an answer to a request for a statement of why Mr. Martin would not be able to join the Copiah Horse Guard. This was just the first of many requests to reach Pettus’s desk once the war was underway. What makes it significant for our purposes, though, is that Mrs. Martin is writing it because Mr. Martin did not want to. She was asserting herself on behalf of her family and her health to keep her husband at home despite the pressures of their community, the state, and the Confederate nation.

Finally, in early April 1861, just one day before Confederates fired on Fort Sumter, Sarah P. E. Simmons, a teacher of 20 years, contacted Governor Pettus. She was applying for a scholarship to the University of Mississippi on behalf of her son, Jeremiah Ellington. His father, Sarah Simmons explains, was killed by someone who held a position of authority. She feared that this person might use leverage to deny Ellington’s application. Simmons included several references in the hope that Pettus would grant the scholarship. Despite the fact that conflict abounded, Sarah Simmons does not appear to have been affected by the rage militaire that inspired so many enlistments that spring. Instead, she hoped her son would be able to attend college so he “may prove worthy of this his native Sunny Land.”

Looking at letters sent to the governor of Mississippi before the outbreak of the Civil War gives the reader a glimpse of how middling and upper-class women of the state asserted their priorities and sought to protect their families. They advocated for love, on behalf of their children, for the betterment of their own financial situations, and a better quality of life. We also have a case where similar motivations may have influenced the actions of a free woman of color. Though the letters in this collection from women before the war are few, it shows a precedent of their political engagement in an increasingly politically charged environment. The next post will show how women’s engagement—of all classes— expanded during the war and analyze the impact of these developments.

[1] For more on Mississippi antebellum laws regulating the rights of free people of color, see this essay at Mississippi History Now; see also Ted Maris-Wolf, Family Bonds: Free Blacks and Re-enslavement Law in Antebellum Virginia.

[2] Woody Holton “Equality as Unintended Consequence: The Contracts Clause and the Married Women’s Property Acts.” The Journal of Southern History 81, no. 2 (2015): 313–40. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43917912.

Sarah West is a Ph.D. student at the University of Southern Mississippi and the Assistant Editor of the Civil War & Reconstruction Governors of Mississippi Project. She earned her M.A. in History from California State University, San Bernardino in May of 2022 and served as a 2021 Summer intern on the CWRGM project, which inspired her Master’s thesis, titled The “Honorable” Woman: Gender, Honor and Privilege in the Civil War South.

Leave a Reply