By DeeDee Baldwin

In the early months of 1871, Mississippi Governor James Lusk Alcorn received letters from three young Black men: George Fulcher of Eggs Point, Albert Snowden of Lauderdale County, and G. A. Watkins of West Point. All three letters are poignant examples of African Americans embracing both their new citizenship—including the right to address the governor directly—and their new access to education and literacy. The letters are difficult to read due to the irregular handwriting and spelling that would be expected of men who had only recently been able to enjoy the right to education, but that only adds to their power.

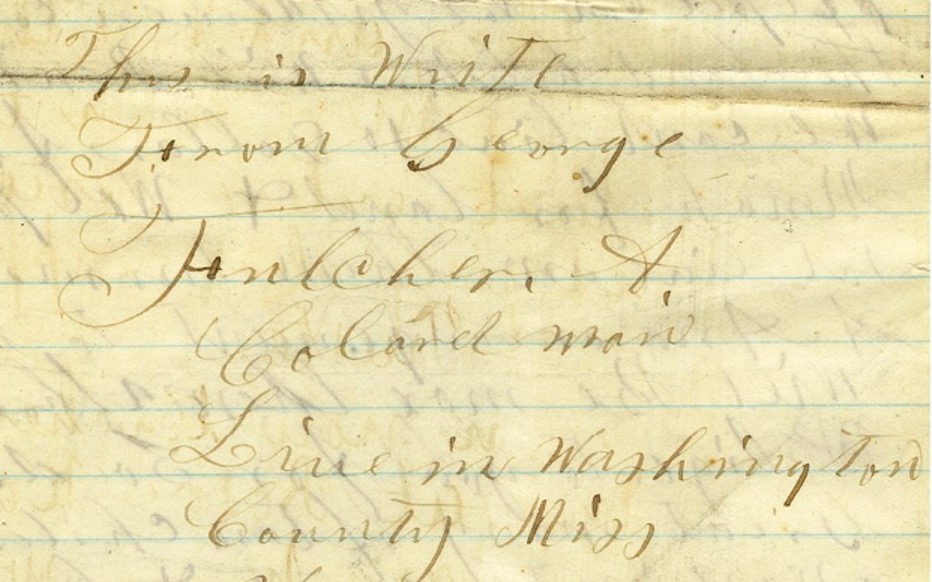

On January 19, George Fulcher of Washington County took his “Pen in hand To drop [Governor Alcorn] a few lines” about the difficulties faced by the people in his community. According to the 1870 census, Fulcher was a farm hand who was born in Mississippi around 1840 and lived near Eggs Point with his wife, Polly, and two young children. Fulcher hoped that Alcorn “will Not Be orfended at my Bold undertakeen for the laws Are made By you in this State & we poor colord peepel can Not git a liven.” The landholders are charging too much for rent, he writes, stating in language that is both colloquial and evocative, “the Skilets are rusting for the wont of some Thing to put in them.” He suggests that Alcorn appoint someone to take care of things, and he maintains that these poor people could “Rase Stock for the goverment if . . . the govenment Will give them a Start.”

Albert Snowden was only about nineteen years old when he wrote to Alcorn on March 19; the 1870 census of Lauderdale County lists him as a student born circa 1852. In his letter to the governor, the young man expresses his concern about violence and unrest surrounding the fiery riot in Meridian earlier that month. (More information about the riot can be found here.) Snowden attributes the unrest to troublemaking “whits from alabama.” Like Fulcher, Snowden acknowledges both his boldness in writing to the governor and the governor’s obligation to serve the people: “I hope you will Knot Think hard of me for this For if we dont look forth to the Gover, and the Leg a lacor [legislature] of the State who will we look to.” Snowden went on to enjoy a long life as a farmer in Livingston, Madison County, where he was documented on the 1880-1920 censuses. He had at least eighteen children with his first wife, Octavia, and second wife, Ida. The census tells us that he owned his home and farm.

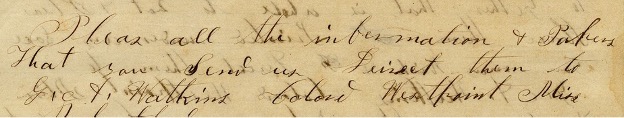

G. A. Watkins, a laborer born about 1840, according to the 1870 census in West Point, wrote to Alcorn on March 17 to request any printed material that the governor might be able to send him: “all the Papers you has & Got no uce for them Pleas Send them We Want & Nede Every thing that We Can get for infermation for our voters in this County.” Watkins worries that the Democrats are misinforming people and “making them beleve that the Republicans ant Doing Nothing for the Colord Race,” and he wants to set up a club to organize and educate voters. He tells Alcorn that the people are suspicious of anything that doesn’t come directly from the governor. The letter is cosigned by Qinson Petty and E. R. Atkins.

One of the myths that arose around Reconstruction was that formerly enslaved people were unprepared for the privileges of citizenship. Many White Americans claimed that these Black men were too ignorant, too amoral, too intellectually inferior to participate in government. Letters like these, along with many petitions that bear African Americans’ signatures, show that they were more than ready and willing to exercise their citizenship, confronting the racism and poverty described in their letters to reach for something more.

We are fortunate to have these documents at all. Until recent years, archives and museums prioritized white voices, neglecting to collect materials that documented the everyday experiences of people of color. These men’s letters were saved as part of a governor’s papers, but one has to wonder how many more letters like them—to the governor, to mayors, to their representatives in the legislature—were lost. Just over 150 Black men served in the Mississippi legislature from 1870-1894, and the CWRGM collection includes many documents by and about them. But we can only imagine how many of their constituents’ letters, to say nothing of their own papers, have been lost to us.

George Fulcher, Albert Snowden, and G. A. Watkins were not legislators. They were ordinary men of their time and place. But they were also extraordinary. Not only had these three men likely learned to read and write as adults in the few years since emancipation, but they were bold enough to use their pens to demand the attention of their governor, shining a light on the problems and struggles they saw around them. They now had a civic voice, and they now had a written voice, and they were determined to use both.

DeeDee Baldwin is the History Librarian at Mississippi State University Libraries, joining the faculty in 2017 after ten years working in the Manuscripts division. She is a past president and current board member of the Society of Mississippi Archivists, and she will soon be a co-chair of the Association for Documentary Editing’s Education Committee. Her website, Against All Odds (link https://much-ado.net/legislators/), documents the lives of over 150 Black men who served as legislators in Mississippi during and just after Reconstruction.

Leave a Reply